Excitement built as Spring approached. The International Wildlife Conservation Society (IWCS) under the leadership of Executive Director, Peter Byrne, firmly established his Base Camp in my hometown of The Dalles, Oregon.

There were other Bigfoot hunters working the Cascade Mountains in those early years of Bigfoot hunting. Unlike today, the hunters were, for the most part, unknown thrill-seeking entities, vying to be first to prove the existence of a hairy cousin of man and ape. All hunters were territorial and projected a sense of competitiveness rather than camaraderie. Peter clearly had the advantage over other hunters of the day. He was well funded and able to move his operation to choice locations, set up camp, and stay for as long as necessary to interview eye witnesses and examine evidence. None of the other hunters, being little more than weekend warriors from their fulltime employment, had that capability. Further, Peter had built a network through county Sheriff’s departments that provided quick notifications in the event of a sighting. There was little doubt they were happy to pass the investigation to “Professional Bigfoot Hunters,” if there were such a thing.

Whenever possible, I donated my time helping prepare for the first major event, an area observation of Crates Point. Peter had on his agenda, the construction of a blind on top of Table Mountain that overlooked the canyon that led to the Point. Peter had obtained permission from the owner of a rarely used rock quarry on the east side of Table Mountain to park our vehicles and transport supplies to the top of the barren mountain. The quarry had a gate we could lock, which provided us a sense of security for our vehicles, while we were engaged in watching the opposite side of the mountain.

On a pre-scheduled Saturday, we, a work party, assembled early in the morning at Base Camp. Peter had at his disposal two four-wheel drive Scout’s on loan from International Harvester for field research. They were handy vehicles for searching off road and hauling a great deal of equipment, but for transporting planks to roof the blind, my three-quarter ton pickup was better suited.

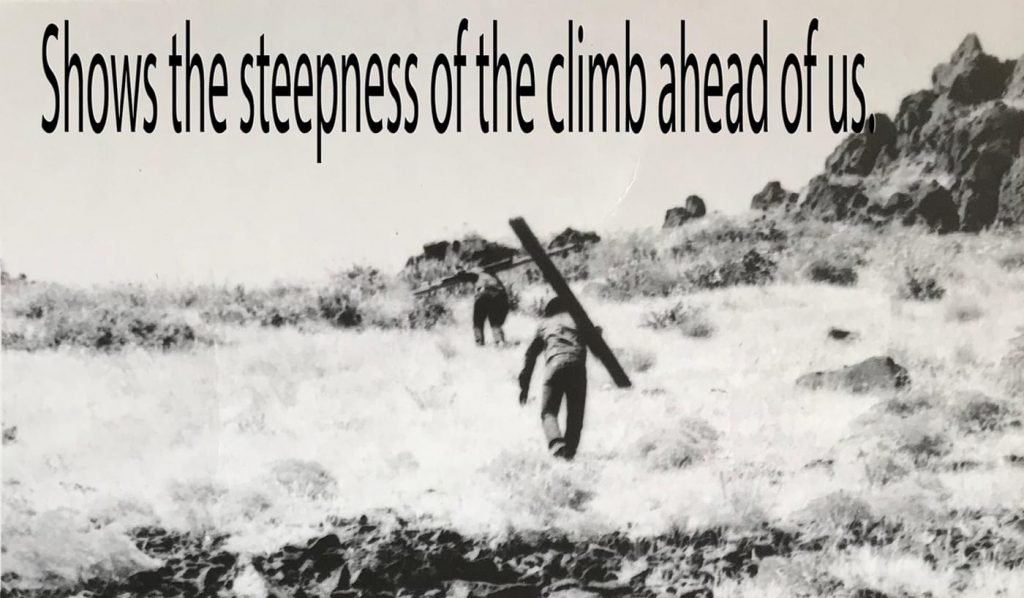

We arrived at the quarry and began our trek to the top of the mountain. Dennis and I started off with planks over our shoulders and returned to tote the heavy canvas tarp to the top.

Once on top of the mountain, we dropped building supplies and gear near the area where Peter suggested we build. Before the day was over, we would make three more trips up and down the mountain. Rather than take breaks from traversing the hillside, we broke up the trips by selecting flat stones on top of the peak to build the face of the blind.

At one point, I picked up a stone, large and flat on one side, then quickly thrust it back to the ground. Immediately I looked to see if anyone saw my demonstrative move. I’d been caught! My abrupt action had been seen by Peter. Killing a creature, large or small, would not set well. After all, it was a conservation society that I had volunteered my time to assist. I made sure other workers knew to watch for rattlesnakes. Under the rock I’d picked up were about a dozen little rattlers. I had lifted the rock far enough from the ground to see snakes swarming from the nest, I put the rock down. Whether Peter was aware that an eight-inch long rattler was as dangerous as a full-grown one, I didn’t know, but they are born with venom ready to attack to defend themselves. I’ve never begrudged nature protecting its own if it allowed me the same measure of respect.

After two days of construction on the blind we made modifications for comfort to the original design. Would the blind stand up to the notorious winds of the Columbia River Gorge that had tossed tractor-trailer rigs on their sides at Crates Point? We secured the top as best we could, knowing it would likely end up in the quarry if we had a hard blow.

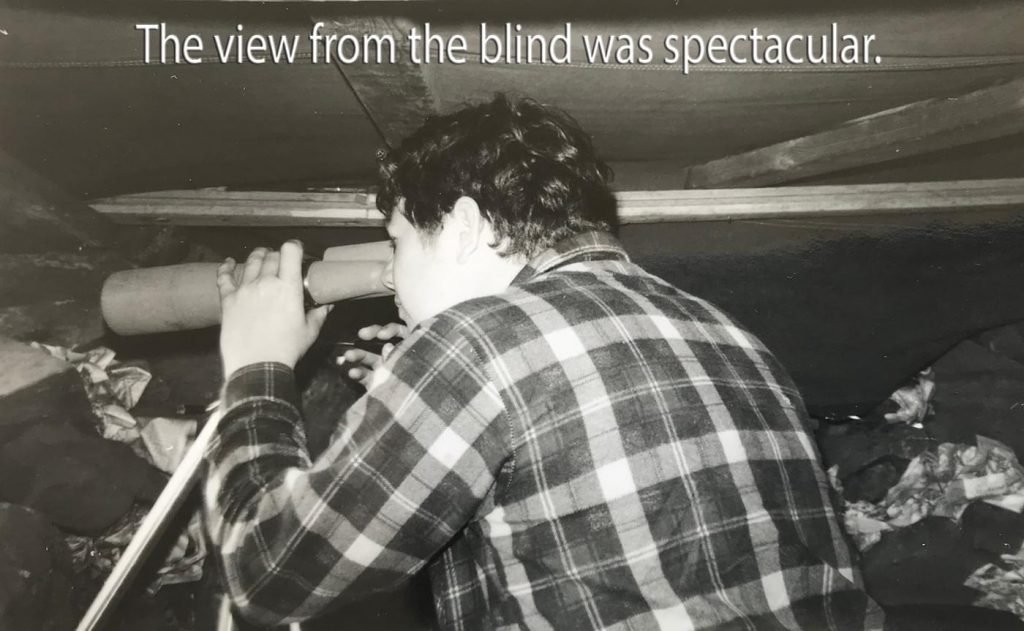

Using binoculars and a spotting scope we had the ability to see the rocky crag that separated the overgrown field from upper meadow. Much of the hillside was covered by a layer of golden grass, scrub oak, and barren of trees. Our observation would focus on this area. If a hairy apelike creature entered the forested area which circled the top of the hill like a bowl haircut, we would likely lose visual quickly. Our goal was to alert the capture team through our handheld CB radios and direct them to the target. The team engaging the Bigfoot were outfitted with two capture weapons that resembled a breech load .410- or .20-gauge shotgun with a tranquilizer dart and hypodermic needle. The ballistic syringe was loaded with a paralytic and sedative enough to bring down a lowland gorilla. The downside to using a capture gun were many. The distance a hunter had to be to the target for deployment of the dart was about thirty-yards. If the Bigfoot riled the hunter’s life was in peril. Fortunately, if the dose was enough to knock the animal out the capture team only had to stay out of Bigfoot’s grips for forty-five minutes when the sedative had worked its magic.

We picked up two additional volunteers for the observation, Jim Day and Darrell Buckles. Both men were local to The Dalles and had years of experience backpacking and game hunting. Peter analyzed the previous sightings and determined the coverage would be late afternoons through the early morning hours after daybreak.

It was logical why we were watching the canyon. Four out of the five most recent years there had been Bigfoot sightings within a two-mile square radius of Pinewood Mobile Manor. From on top Table Mountain we had a clear view over most of the area in question. But it still begged the question, why Crates Point?

Peter explained that we were dealing with unknowns, but if Bigfoot existed it was possibly nomadic. If this was the case, and it was crossing the Columbia River, Crates Point made sense. The location was not only one of the narrowest spots along the river, but it had three small islands to break up the swim. Once on the Washington side of the river and into a canyon, it likely would not be seen entering the Klickitat Mountains.

Peter worked the blind for a few days, without involving the rest of us, to get a feel for what we could see and the blind’s limitations. A few weeks into the watch we were joined by a University Professor and two students that took over some of the watch duties. Near the end of our weeks of observation, an Army Specialist joined in the search with a large 40mm Night Observation Device (NOD) on loan from the government which was used during a portion of the night watch.

The investigating team worked tirelessly to make history that Spring with proof of Bigfoot’s existence. The level of proof required more than a glimpse, another video, or howling in the dark of night on a lonely hillside. We had to have conclusive evidence.

One day, in the waning days of the observation, I picked up on movement in the tree line. It wasn’t a Bigfoot, but a big dog running loose. I continued to watch through the spotting scope until I saw a man in an orange jacket with the dog. I contacted Peter and he followed up only to discover the man was part of another group of Bigfoot hunters who had set up their base camp smack-dab on a game trail that was the primary route down Crates Point. If that wasn’t enough to run a Sasquatch off, and spoil our observation, the nightly bonfires they made would.

As Sasquatch hunting goes, we either missed the main event or it chose another route down to Crates Point because of the Bigfoot hunters interference. Of course, there was a third possibility which none of us wanted to entertain at the time. Perhaps Bigfoot didn’t show because no such creature lived in the modern-day Pacific Northwest. There were hundreds of unexplained sightings. It was hard to fathom why people who didn’t know each other would take part in an elaborate hoax with nothing to gain from reporting they had seen a Bigfoot. The team maintained an open-mind to the phenomenon.

By the end of June, we had wrapped up the observation and were poised to roll if notified by the Sheriff’s Department, news media, or rumor of another sighting. Our focus changed from a jagged rock point to the entire mountain range from southern British Columbia to Northern California.

If Bigfoot inhabited the region it wouldn’t be long before we received a call, and it wasn’t.

My pickup was outfitted with a CB radio. In the days before cellphones, a CB was a handy option. The crackling of the radio made my heart jump. It was Peter. “We have something can you get away.”

“I’ll be there.”

When I arrived at Base Camp, Peter briefed Dennis and me on an alert he received. “A city official of Lyle, Washington, who wanted to remain anonymous reported to the Klickitat County Sheriff that he was alone and returning form a business meeting in Portland, Oregon, the previous night. He crossed the Columbia at the Bridge Of The Gods on his return home to Lyle. While he drove through the pouring rain, he saw a large brown thing along the edge of the highway and nearly wrecked his car trying to avoid hitting it. He thinks it might have been a Bigfoot. His only description was big and brown.”

Peter made phone contact with the man and went over the details again. Literally there was no change in the information other than providing a mile marker he passed soon after the incident. We loaded up in Peter’s Scout and made our way to the river crossing at Cascade Locks.

Was this a hoax? I didn’t think so. This was a highly credible person who wanted nothing out of the sighting. Not even the mention of his name. Our mission was to locate the spot the clamant identified and find footprints or other evidence to corroborate the sighting.

Interstate 84 runs along the Columbia River on the Oregon side while State Highway 14 parallel’s the river from the Washington side. Travelling the gorge differs from side to side as much as day does from night. Interstate 84 is a modern four-lane road and clear-cut for safety. The opposite is true for the Washington side. Shrouded in uninhabited impenetrable coniferous forests and scenic but forbidding canyons, State Highway 14 snakes along the river’s edge with its narrow two-lane road. Our first order of business was to find the mile post and work our way west. Peter dropped Dennis and me off as planned and we began our walk. Dennis took the south side of the road looking for tracks or any disturbance on the edge of the road where the city official said he nearly ran off the road. I worked the north side primarily looking for tracks in the steep embankment where the road had been cut through the hillside. The ground was wet and the hillside moist and loose. Tracks would be easy to spot and follow if we were so lucky.

The walk was slow, taking in the possibilities of every disturbance of dirt or tree limb downed near the road. We hadn’t walk far when we saw Peter stopped on the shoulder of the eastbound lane.

When we came up to where Peter stood, it was easy to see what he’d spent his time looking at. Tire tracks had recently cut a deep groove into the soft side of the road’s shoulder and the culprit that the claimant almost struck still stood there. Not far from the fresh tire track was the trunk of a tree, bark less, and deep brown from the recent rain. The tree had been lopped off from the trunk. What was left of the tree was around ten-foot-tall and no threat to motorists with the roots imbedded under the roadway.

Pictures were taken of the tree then we headed out to find a diner and a cup of coffee to help overcome the disappointment before our return trip to The Dalles. This call, like all calls whether they produced evidence or not, was a quest for truth.