What danger is the American democracy in, if any?

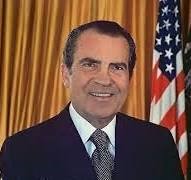

Politically, the changes in GOP/evangelical politics began with a swing of conservative evangelicals to the Republican Party, to Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy, and to outspoken and heavily “patriotic” and fellow Republican leaders like Senator Barry Goldwater, who apparently were in concert with the evangelicals’ religious views. Richard Nixon and the Southern Strategy solidified the Republican Party as the party of discontented White evangelicals who were coming to fear the civil rights movement and the apparent “culture wars” as a threat to their traditional lifestyle and native-born privileges. In the 1964 presidential election, Republican candidate Barry Goldwater won the then-traditionally Democratic states of Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Mississippi. This developing religio-political alliance solidified with opposition to federally mandated desegregation. In the 1968 presidential election, Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey lost every Southern state to Republican Richard Nixon and to Independent candidate George Wallace, an avowed racist and segregationist.

The 1960s ushered in another set of rapid cultural and political changes. Local controversies over textbooks and sex education in public schools, forced busing, the tax-exempt status of religious schools, and gay rights raised concerns. Activists motivated by their religious beliefs began grassroots efforts to promote their causes locally, and their efforts eventually captured national attention.

By the 1970s, high-profile Christian leaders began to talk more publicly about politics, and several founded organizations, such as Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, the Religious Roundtable, and Christian Voice, to encourage theologically conservative Christians to get more involved. Over time, these organizations and activists became known as the “Christian Right”, a reference to their right-of-center political leanings and intentions.

Still–in the 1970s–evangelicals tended to support Democrats. Jimmy Carter’s successful presidential campaign in 1976 connected well with evangelicals who were growing more active on individual political issues but were not yet particularly active in party politics. Carter–a Southern Baptist Sunday School teacher–spoke often about his faith and described himself as “born again.”

During the Carter presidency, however, evangelical support began moving toward the Republicans and away from Democrat liberal government policies. By the late 1970s, they saw the importance of the abortion issue, Roe v. Wade, and its connection to central Christian teachings. By the 1980 presidential election, abortion was a centerpiece of Christian Right politics.

Ronald Reagan’s campaign and the Republican Party recognized the importance of evangelical voters and actively sought their backing, more than ever before. Beginning in 1980, the Republican platform included planks supporting organized prayer in public schools and defining human life as beginning at conception; and the party began to embrace the terms “pro-family” and “pro-life” to describe its agenda. Evangelical voters responded with strong support for Reagan in 1980 and 1984.

By the end of the 1980s, evangelical voters had become an essential part of the Republican base. Republican candidates and party leaders actively sought evangelical voters, crafting issue appeals to win their support. This has only intensified as the 2024 election year drags on. By the 1990s, more decentralized organizations were emerging within the evangelical base that built strong networks of supporters and emphasized grassroots mobilization: the Christian Coalition, founded by religious broadcaster Pat Robertson after his unsuccessful 1988 presidential bid. In 1995, the Christian Coalition boasted 1.6 million members and 1,600 local chapters. Most of the largest and best-financed Christian advocacy organizations were ideologically conservative, but there were still other Christian groups that emerged offering an ideological counterpoint and raising more progressive concerns. That middle ground Christian voice is still heard in counterpoint to the evangelicals.

The January 20, 2001 election of President George W. Bush energized conservative evangelicals. His open discussion of his personal faith along with his positions on social issues and judicial appointments appealed to them. With Republicans in control of the presidency and Congress, evangelical leaders looked forward to many political victories.

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, shifted the policy agenda in Washington. Domestic issues of greatest concern to the Christian Right were eclipsed by national security and foreign policy. In 2004, Christian Right leaders worked aggressively for Bush’s re-election, expecting that Bush would prioritize their agenda in a second term.

By the middle of Bush’s second term, however, some former supporters openly criticized him for neglecting domestic issues, especially battles against abortion and gay marriage. Some evangelical leaders openly questioned the effectiveness of their strong connections to Republicans, suggesting that the party was taking the evangelical voting bloc for granted.

A new generation of activists was gaining influence in many issue advocacy groups. With backgrounds in politics–not religious leadership–they came on with a more pragmatic approach. Their leadership style moved away from bold demands for change, looking instead for more incremental changes that had a greater likelihood for success. In the early 2000s, this approach led to a series of legislative victories, including the passage of three pro-life bills.

Candidates and incumbents saw that they faced a difficult task to win over the evangelicals in that era. Republicans had to seek to maintain and build their evangelical base without losing support from less religious voters, while Democrats needed to try and expand their appeal by speaking about religion without alienating secular voters. That is most certainly part of the election puzzle of 2024. Certainly, there is a “religious right” and will likely always be; most evangelicals vote conservative; but, interestingly, less than a fifth continue to identify themselves as members of the “Religious Right” as so defined.

Also, in practicality, there are more aficionados of the “religious right” than the Old Confederate South Bible belt WASPS [White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans] which usually come to mind.

- Catholics: Even as late as the early 1970s, most evangelical leaders were almost as anti-Catholic as they were anti-secularist and anti-communist, part their political model based on restoring the old Protestant-dominated social order. But by 1979, evangelical leaders began making major long-term investments in alliances with Catholics. They jettisoned the confessional Protestantism of the old social order for a broader “Judeo-Christian” moral traditionalism, at least for the pragmatic purposes of achieving and maintaining political clout. That increased power is likely to make a contribution to the crucial 2024 election year.

- Fundamentalism. What had been an acrimonious divide between “fundamentalists” and “evangelicals” was also largely mitigated as political pragmatism began to win out. Up through the early 1970s, the prevailing political model had fueled hostility between these subgroups. The evangelical desire to act as moral guardians of America’s social order clashed head-on with fundamentalist fears that playing such a role would inevitably compromise doctrinal purity, just as it had for the mainline. Tensions along these lines remain to this day; but in 1979, they suddenly became subordinated to what were viewed as more urgent moral, cultural, and practical, political concerns. This opened the door to unprecedented levels of evangelical cooperation and of political mobilization among fundamentalists. For Republican populists, it was as win-win.

Race. White evangelical leaders as a group–who had turned a blind eye to racial injustice–got on board for civil rights. Until the 1970s, many White evangelical leaders supported the racial status quo uncritically, in large part because they saw themselves as guardians of the existing social order.

Partisanship. Perhaps most important change in the American political scene was the new willingness of evangelical leaders to move to one political party. Under the Religious Right model–almost without realizing what they were doing–evangelical leaders extensively subordinated the life and religious culture of their church to the political interests of the GOP.

Evangelical leaders muted their criticism of immoral personal behavior in order to avoid embarrassing Republican leaders. That paved the way for acceptance of Donald J. Trump who appealed to their baser rural, red neck, culture and mores, even though his scandals and utterances were at odds with their family lives and traditions.

They also began to temper the more socially extreme aspects of their theology, such as the exclusivity of salvation in Christ. Southern Baptist Convention President Bailey Smith complained that political rallies typically feature public prayers from both Christian and Jewish clergy, which implies Christianity and Judaism are the same, when in fact only those who trust Christ have God’s favor, a contention previously core to evangelical doctrine. Robertson and Falwell made complex, obfuscatory “clarifications” to avoid media fallout damage to their favorite Reagan—a major compromise that has carried over to the 2024 election and Donald Trump.

That religio-political partisanship coincided with increased levels of hostility from the Democrats leading to the great schism widening almost daily in 2024. However, evangelical leaders did not want to appear to be uncritical cheerleaders of the Republicans or to alienate their former allies, the Democrats, unnecessarily. With the next president being elected by a relatively small number of votes, those differences may loom large in 2024.

There are several causations for the change in alliances by the Religious Right; a 1978 IRS proposal to strip some evangelical schools of their tax-exempt status. Evangelicals dropped their opposition to Catholics because they were desperate for allies. Fundamentalists overcame their fear of activism because they were more afraid of societal collapse. Evangelicals went all-in on the GOP in hopes of maximizing their political leverage. A parsimonious explanation for the Religious Right moving so strongly towards political action and voting for the Republicans is that it fits the pragmatic facts. The astonishing steamroller effect of libertinism in the 1960s and 70s produced something like a panic. Evangelicals saw America rushing ever more rapidly toward cultural and anti-religious catastrophe. The tipping point seemed to be on the horizon.

“God is angry with us as a nation,” Falwell declared. “I have a divine mandate to go right into the halls of Congress and fight for laws that will save America.”

The moral panic led to the idea of strategic shifts for evangelicals cum politicos. That theory denies that evangelical mobilization was primarily a defensive response to anti-evangelical government legal, policy, and regulatory, discrimination against evangelicals. In general, evangelicals have cried, “They attacked us! We’re only defending ourselves!” The importance of “unfair” government action towards right leaning political religious people and institutions in light of the more truly religious concern about moral decay and its danger to the United States. It was comparable to the threat of Communism, Darwinism, and Atheism.

In the end, evangelicals were political pragmatists. They shifted evangelical politics for strategy: evangelicals were prompted to desperate measures by what they saw as desperate times, while still maintaining that their basic assumptions and goals did not really change. Looking at the history of the tens and twenties of the 21st century, the Religious Right has become a triumphalist movement, with new alliances, voter enrollments, and a genuine prospect of new a new roll to victory. The Religious Right saw the future with them putting the enemies of morality under its heels and saving America.

“We have . . . enough votes to run the country,” Pat Robertson announced in 1979.

It was then, and is now, heady stuff. They are on the way to taking over the world. Now—2024—they can see a grand horizon of making America great again, and they have a charismatic champion. Everything else in this election year pales in comparison.

But the Religious Right was already declining in power by the mid-1980s, and it withered throughout the 1990s. After the early years, it accomplished few of its legislative priorities. Politicians deftly extracted money, votes, and volunteer time, from evangelicals while delivering little of substance. The best it could do was maintain a political stalemate with libertinism.

Some ardent evangelicals think the Religious Right is now essentially in control of the GOP, but a more sober and deeper inspection indicates that it is the self-promoting politicians who are becoming firmly seated in the driver’s seat. Most aspiring politicians “promote people of all faiths” or even “no faith” as their path to political election and reelection. It is somewhat unclear what the GOP candidate does feel in that regard, but it is certain that he is willing to antagonize the “others”, especially Muslims, to maintain the cohesion of his base with him—the “true Judeo-Christian” moral tradition and correct moral choice for America.

The continuing right-wing fervor has resulted in extensive damage to the American culture. We are exposed to a great deal of political manipulation with what is beginning to appear to be a permanent division in the American tapestry. In addition, the shift right has reinforced a widespread cultural perception that the gospel of Christ is a right-wing political program, driving people away from the Protestant church or even any religion at all.