Occasionally, a little nugget of history sneaks into your day and refuses to leave. You read it once, smile, and then catch yourself telling it to the next five people you talk to — because it’s just too good not to share.

Here’s one of those nuggets.

Long before the neighborhood bookmobile, before card catalogs or whispered shushes in the reading room, there was a king named Ashurbanipal. This was in ancient Assyria — around the 7th century BC — and Ashurbanipal wasn’t just any ruler. He was a reader. Not the casual, “Oh, I’ll finish that novel someday” type. He was a book lover on a mission.

His palace in Nineveh housed one of the earliest known libraries in the world. And this wasn’t a modest little shelf tucked in the back of a palace study. We’re talking thousands of clay tablets carefully arranged and cataloged, inscribed with everything from religious rituals to medical knowledge, history to omens.

But here’s the twist: Ashurbanipal’s library had a curious policy.

You didn’t have to return the books.

Why? Because these weren’t ordinary books. They were sacred possessions of the gods. The clay tablets weren’t borrowed and brought back. They were consulted. Respected. Revered. Imagine going into your local library today, checking out a book, and being told, “Oh no, don’t bring that back. It belongs to the divine.”

It changes the whole experience, doesn’t it?

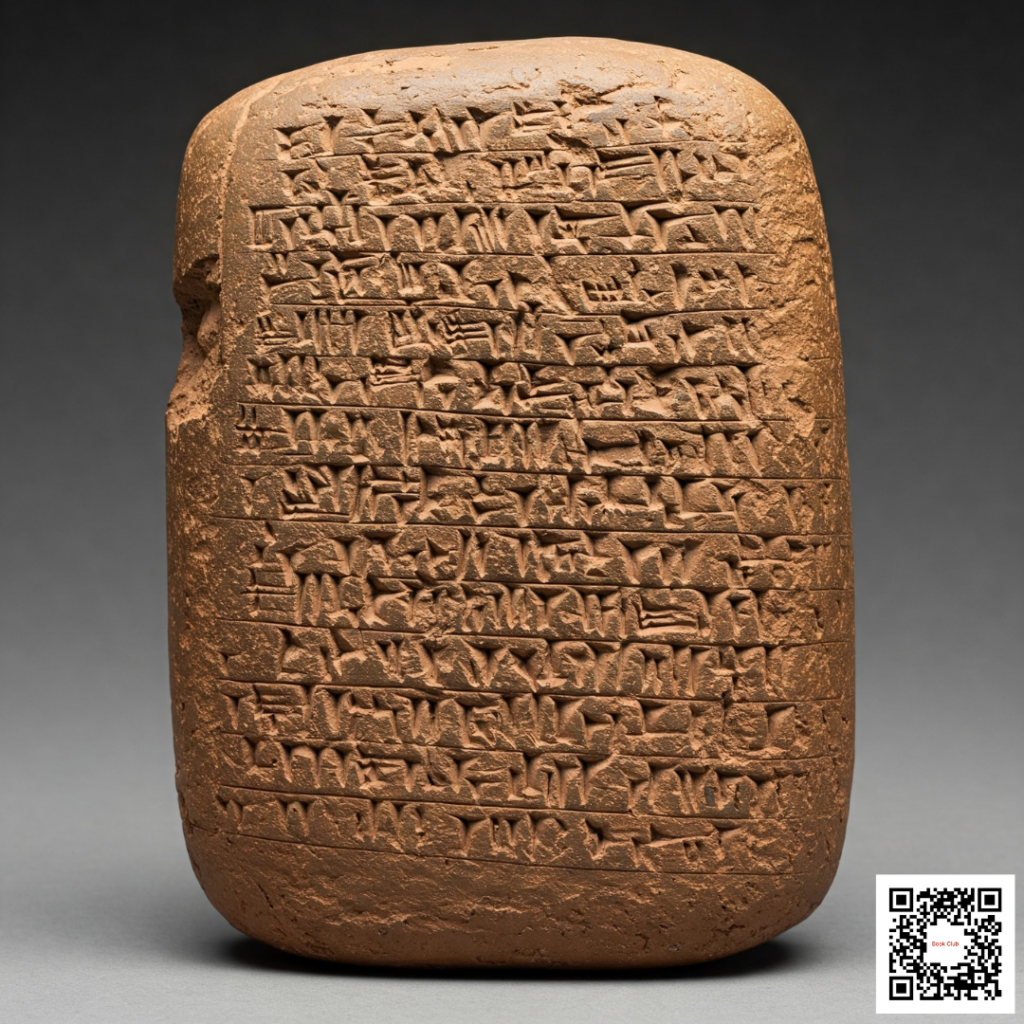

The tablets were written in cuneiform, that wedge-shaped script etched into wet clay and baked dry under the sun. Each one preserved the knowledge of the time in a form as durable as heavy. Drop one of those on your foot, and you wouldn’t need a bookmark — you’d need a cast.

Ashurbanipal’s collection eventually formed the backbone of our modern understanding of Mesopotamian civilization. When archaeologists unearthed the ruins of his library in the mid-1800s, it was like opening a time capsule sealed by the ancients. Among the finds? A version of The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest stories ever recorded. That’s like stumbling across a first edition of Moby-Dick — if it had been carved into stone and buried for 2,600 years.

What I love most about this story is how it reminds us that the desire to preserve stories, share wisdom, and create a space for learning is as old as civilization itself. Ashurbanipal’s library might not have had beanbag chairs or a children’s story hour, but it had purpose, reverence, and a view of reading as something worth etching into stone.

Something is charming about the idea of a “no return” policy that isn’t lazy but sacred. Today, we get gentle email nudges when our books are overdue. In Nineveh, the rules were spiritual: return the tablet, and you’re challenging the gods’ will. Keep it, and you’re merely continuing the sacred chain of knowledge.

It’s strange to think that we’ve gone from divine clay tablets to eBooks that disappear when your library loan expires. From gods to glitches. Still, the mission hasn’t changed. We read because it connects us — across time, cultures, and even empires that no longer exist.

So, remember King Ashurbanipal and his grand clay collection the next time you pull a book off the shelf. Think about those heavy tablets, the scribes hunched over with styluses, the sense of wonder they felt recording their world for future readers who wouldn’t arrive for millennia.

And smile — because you’re part of that same long, marvelous tradition.

Who knew that fun trivia about a Mesopotamian monarch could make you feel more connected to your bookshelf?

Want more fun trivia like this? Stick around — there’s always another literary oddity waiting to be discovered! Readers and Writers Book Club, where we dig into the fascinating lives of authors, swap trivia about literary legends, and explore hidden stories behind the books we love. If this bit of trivia intrigues you, wait until you hear what else is hiding in the pages of history. Come on in — I promise, there’s always room for another curious mind!

Where every reader is a friend, and every author is approachable: https://bit.ly/41vgvKh