Article I. Three British Wars with Funny Names and Some Importance

Historically—during Great Britain’s dominance of the seas—the British fought innumerable sea battles and wars with a host of temporary enemies and for a large number of disparate reasons, both noble and ignoble. Three of them come to mind and will be presented in a series of articles about each of them. They are: The War of Jenkins’s Ear, The Pig War, and The Shortest War in History [the Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896].

WAR OF JENKINS’S EAR

Background:

British: The War of Jenkins’ Ear, Spanish: Guerra del Asiento, [War of the Agreement] was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Great Britain and Spain. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It was related to the 1740–1748 War of the Austrian Succession. The name was coined in 1858 by British historian Thomas Carlyle and refers to Robert Jenkins–captain of the British brig Rebecca–whose ear was allegedly purposely severed by Spanish coast guards while searching his ship for contraband in April, 1731.

The war has usually been described as a dispute between Britain and Spain over access to markets in Spanish America including the Caribbean. More recent historians argue trade was only one of a number of issues, including tensions over British colonial expansion in North America. They suggest the decisive factor in turning an economic dispute into war was the domestic British political campaign to remove the Whig government led by Robert Walpole, Prime Minister since 1721.

The 18th century economic theory of mercantilism viewed trade as a finite resource, and countries could only increase their share at the expense of their rivals. That theory led to wars being fought over purely commercial issues, sometimes given euphemistic or obfuscatory names for their violence for the sake of greed. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht gave British merchants access to markets in Spanish America, including the Asiento de Negros, a monopoly to supply 5,000 slaves a year. Another was the Navio de Permiso, permitting two ships a year to sell 500 tons of goods each in Porto Bello in Panama, and Veracruz in Mexico.

However, the value of these limited rights was insignificant compared to the trade between Britain and mainland Spain. British goods were imported through Cadiz, either for sale locally or re-exported to Spanish colonies, with Spanish dye and wool going in the other direction. Much of the time the trade was amiable. The slavery asiento itself was marginally profitable and has been described as a “commercial illusion”; between 1717 and 1733, only eight ships were sent from Britain to the Americas for the purpose. Many British, including especially American colon-ists made their livings by transporting smuggled goods that evaded customs duties, demanded from Spanish colonists creating a large and profitable black market in favor of the British colonists.

Accepting that smuggling was too lucrative and widespread for the Spanish to stop altogether, the Spanish tried to manage it with a “wink-wink, nod-nod” semi-laisse-faire approach and sometimes even used it as an instrument of policy. However, during the 1727-1729 Anglo-Spanish War, French ships carrying contraband were let through, while British ships were stopped; and severe restrictions imposed on British merchants in Cadiz. This was reversed during the 1733- 1735 War of the Polish Succession, when Britain supported Spain.

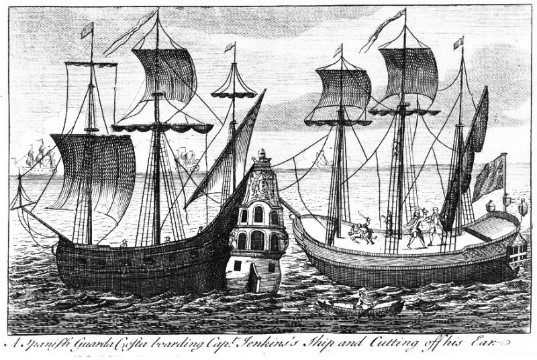

Under the 1729 Treaty of Seville, the Spanish were allowed to board British vessels trading with the Americas and check them for contraband. On April 9, 1731, the British brig Rebecca, captained by Robert Jenkins of the East India Company carrying a possibly illegal cargo of sugar from the British colony of Jamaica to London, lay becalmed off Havana when she was overtaken by the 16-oared Spanish sloop San Antonio, captained by Juan León Fandiño. The Spaniards fired several shots in the direction of the Rebecca and demanded to search her for contraband. They motivated Jenkins’ cooperation by hoisting him up the mast three times by a rope tied around his neck then casting him down the forward hatch. A report in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette for October 7, 1731 reported: the Spanish Lieutenant Dorce Fandiño himself, seized Jenkins, “took hold of his left Ear, and with his Cutlass slit it down; and then another of the Spaniards took hold of it and tore it off, but gave him the Piece of his Ear again, bidding him carry it to his Majesty King George”.

While rather tepidly deprecating such treatment, the Royal Naval commander in Port Royal admitted those involved in what he described as “clandestine trade” could not complain if their cargoes were confiscated and often indulged in similar such violence themselves. Such incidents were seen as the cost of doing business, and it was quickly forgotten after the Spanish eased restrictions in 1732.

Tensions increased after the founding of the British colony of Georgia in 1732, by threatening Spanish possessions in the Caribbean Basin which Spain also considered a more important threat to Spanish Florida, vital to protect shipping routes with mainland Spain. For their part, the British viewed the 1733 Pacte de Famille between Louis XV and his uncle Philip V as the first step in being replaced by France as Spain’s largest trading partner. Tensions accelerated after a second round of Spanish “depredations” in 1738 led to demands for compensation to Great Britain and its merchants. Tory-backed newsletters and pamphlets presenting the Spanish violent incidents as being inspired by France, Britain’s of-and-on-again chief adversary. The opposition Tories make a complex linkage implying the sitting government’s failure to act was due to George II’s concerns over exposing Hanover to French attack.

Response to the severed ear incident itself remained luke-warm until opposition politicians in Parliament–backed by the South Sea Company–used it seven years later to incite support for a war against Spain, hoping to improve British trading opportunities in the Caribbean. The incident reported to Parliament was widely and avidly circulated then.

The Parliamentary committee learned that the incident that gave its name to the war had occurred in 1731, off the coast of Florida, when the British brig Rebecca was boarded by a party from the Spanish patrol boat La Isabela, commanded by the guarda costa [here read, privateer] Juan de León Fandiño. After boarding, Fandiño cut off the left ear of the Rebecca’s captain, Master Mariner Robert Jenkins, whom he accused of the crime of smuggling.

Fandiño told Jenkins, “Go, and tell your King that I will do the same, if he dares to do the same.”

In March, 1738, when Jenkins returned to England–with his ear pickled in a bottle–it had tremendous effect on the country. A committee of the House of Commons summoned Jenkins to appear before them, and told him to produce the ear, which he duly did.

When asked “What did you do?”

Jenkins replied, “I commended my soul to God and my cause to my country.”

Surgeons in the mid-18th century did not have experience with repair of traumatic total auriculectomies. Most contemporary surgeons favored auricular prostheses over surgical treat-ment. Methods for the reconstruction of partial defects were available, and most authors advocated a local post-auricular flap instead of a free tissue transfer. Techniques for repair of defects of the auricle lagged behind those for repair of the nose.

According to some accounts, Jenkins produced the severed ear as part of his presentation, although no detailed record of even the hearing itself exists. The incident was considered alongside various other cases of “Spanish Depredations upon the British Subjects” and was perceived as an insult to Britain’s honor and a clear casus belli.

The event—even its naming—was not nearly so simple and clear. First of all, Frank-lin’s Pennsylvania Gazette for October 7, 1731, stated that it was Lieutenant Dorce who did the auriculectomy [fancy surgical term], not Fandiño. Second, the name of the ensuing conflict did not take place until it was named by essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle, in 1858, 110 years after hostilities ended. Carlyle mentioned the ear in several passages of his History of Friedrich II, 1858. Third, despite his ear’s impact on world history, some British historians doubt whether Jenkins actually did suffer a traumatic auriculectomy at the hands of the Spanish. The eminent contemporary politician and author Sir Edmund Burke doubted his story, calling it the “Fable of Jenkins’s Ears”.

William Cobbett–author of the multi-volume Parliamentary History of England—con-cluded that in all likelihood–Jenkins never appeared before Parliament at all.

Although Spanish accounts did not necessarily deny Jenkins’ injury, they portrayed him as a smuggler and a pirate who deserved his treatment. Indeed, some English accounts acknowledge that Jenkins was a well-known smuggler. Stewart wrote to the Duke of Newcastle in October, 1731: “…but give me leave to say that you only hear one side of the question; and I can assure you the sloops that sail from this island, manned and armed on that illicit trade, has [sic] more than once bragged to me of their having murdered 7 or 8 Spaniards on their own shore”.

Whether Jenkins appeared before the House of Commons in March, 1738 to demonstrate publicly the extent of his alleged injury is also controversial. The House of Commons Journal for 1738 read:

“16th March. Ordered, That captain Robert Jenkins do attend this House immediately” and “17th March. Ordered, That captain Robert Jenkins do attend, on Tuesday morning next, the Committee of the whole House, to whom the Petition of divers merchants, planters, and others, trading to, and interested in, the British plantations in America, on behalf of themselves, and many others, is referred”.

However, the records for the House of Commons detailing the petition on that Tuesday March 21, 1738 did not mention Jenkins at all.

Parliament and the Navy also wanted to retain the lucrative Asiento de Negros giving British slave traders permission to sell slaves in Spanish America, which is why the Spanish called the resulting conflict the Guerra del Asiento. Unsuccessful British attacks in 1741 on the ports of Cartagena and Havana resulted in heavy casualties, primarily from disease, and were not repeated. In support of their campaign against Walpole, the Tories exhibited Jenkins in the House of Commons; and it was not until this point, that the Jenkins ear incident became widely known. The January, 1739 Convention of Pardo set up a Commission to resolve the Georgia-Florida boundary dispute and agreed Spain would pay damages of £95,000 for ships seized. In return, the South Sea Company would pay £68,000 to Philip V as his share of profits on the asiento. Despite being controlled by the government, the British owned company refused; and PM Walpole reluctantly accepted that war could not be avoided. On July 10, 1739, the Admiralty was authorized to begin naval operations against Spain ten days later. A force under Vice Admiral Edward Vernon sailed for the West Indies, finally reaching Antigua in early October. On October 22, British ships attacked La Guaira and Puerto Cabello, principal ports of the Province of Venezuela; and Britain formally declared war on October 23, 1739.