Part VI Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

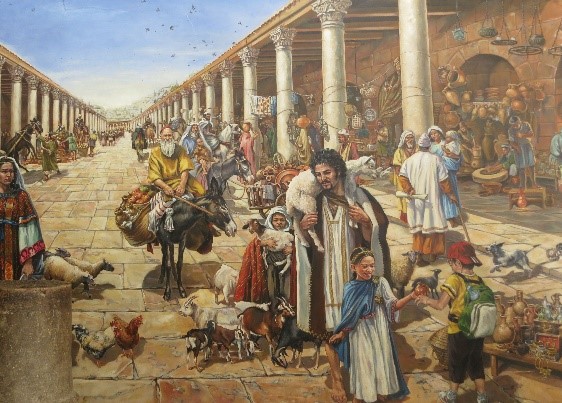

Hellenic Judaism to Christianity [64 BCE], to the Roman era [64 BCE-611 CE] to the defeat of the Romans by the Persians [619 CE]

Hellenic Judaism with Christianity initially emerged as a sect of Judaism and finally as an independent religion by the mid-second century CE. Gnosticism also took hold in the region all in competition with the pagans.

In 391 CE, the Roman era in the Levant began with the permanent division of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western halves. Eastern Roman control over many parts of the Levant lasted until 636 when Arab armies conquered the region. The same area became a part of the Rashidun Caliphate and then known as Bilad al-Sham.

The collapse of the Akkadian Empire saw the arrival of peoples using Khirbet Kerak Ware pottery coming originally from the Zagros Mountains, east of the Tigris River in Mesopotamia. Some Ur seals suggest that this event marks the arrival in Syria and Palestine of the Hurrians, people later known in the Biblical tradition possibly as Horites.

In Judas of the priestly Hasmonaean family, the Jews found a hero-rebel who, with his brothers, succeeded in capturing Jerusalem and cleansing the temple. Judas was surnamed Maccabeus “the hammerer,” an allusion to the telling blows he inflicted on the Syrian army. In 164 BCE, the Jewish community attained religious freedom and in 140 BCE, political independence. Under the Maccabean dynasty of priest-kings, the realm expanded and lasted until the advent of the Romans about eighty years later.

Under the reign of the Hasmoneans [37-70 BCE] the Jewish state was largely composed of Jews. But in 63 BCE, when Pompey came to Jerusalem he began to reverse this process. He allowed the Jews to rule the south and Galilee, but non-Jews ruled the rest of the region. Julius Caesar was Pompey’s rival; and when Pompey was killed in 48 BCE, Caesar prepared new territorial arrangements. He left Antipater–an Idumean–as administrator of the Jewish state. But Caesar’s new arrangements did not last for long. He was assassinated on the Ides of March [the 15th], 44 BCE. Even this did not end Jewish resistance.

Herod was confirmed by the Roman Senate as king of Judah in 37 BCE and reigned until his until his death in 4 BCE, about the time of the birth of Jesus. Nominally independent, Judah was actually in bondage to Rome, and the land was formally annexed in 6 BCE as part of the province of Syria Palestina. Rome did, however, grant the Jews religious autonomy and some judicial and legislative rights through the Sanhedrin. The Sanhedrin–which traces its origins to a council of elders established under Persian rule [333-165 BCE]–was the highest Jewish legal and religious body under Rome. Of all the multitudinous peoples who constituted the Roman world, the Jews were undoubtedly the most difficult for the Romans to govern. Herod repressed the outbreaks against his authority with bloody fury. After Herod, the Judeans continued restive under Roman rule.

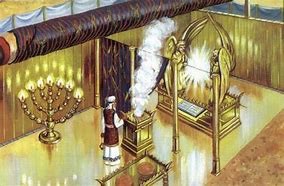

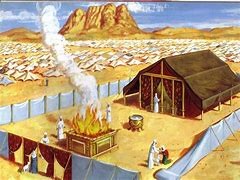

In 67 CE Vespasian–the future emperor–moved against the Judeans from Syria at the head of 50,000 troops and dealt them telling blows. His son Titus carried on the operations against Jerusalem. After a few month’s siege Jerusalem was starved into surrender [70 CE]. The Judean capital was razed, and thousands of its citizens inhabitants were slaughtered. The second Temple—which had been built in 515 BCE–was sacked; the Holy of Holies, was desecrated; and the sacred edifice was completely destroyed.

The Jews gave up their attempts to throw off the Roman yoke, while the Roman government acknowledged Judaism as a religiolicita, its communities enjoying the right to certain exemptions–from military service, for example–and being allowed to exist as juridical entities, to own property, to have their own courts [disguised as tribunals of arbitration], to levy taxes and so on. But, despite these concessions, on two points there was no giving way: the Romans still declined to permit Jews to live in Jerusalem, although restrictions on visits were relaxed, and proselytizing was frowned upon. Within this loosely outlined nexus of official relations, normative Judaism could go on developing.

The last century of Roman rule in Palestine was marked in Judea–as elsewhere in the Roman world–by a political and economic crisis which shook Roman society to its foundation. The crisis in the empire was settled by the energetic measures of Diocletian, a rough soldier who put an end to civil wars and reorganized the administration. Diocletian was the last emperor to see in Christianity an enemy of Rome, resulting in cruel and bloody persecution of the sect.

Emperor Constantine [c. 280-337 CE] shifted his capital from Rome to Constantinople in 330 and made Christianity the official religion. With Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, a new era of prosperity came to Palestine, which attracted a flood of pilgrims from all over the empire. Constantine’s policy was the same as Hadrian’s towards the Jews. They were not allowed to live in Jerusalem; but they made pilgrimage to the western wall of the Temple, and once a year on the ninth of Ab they were allowed into the Temple site to lament its destruction.

The adoption of Christianity as the dominant religion of the empire changed the status of Palestine radically. No longer just a tiny province, it became the Holy Land, on which emperors and believers lavished untold wealth; the former claimants to it, the Jews, were powerless to establish their right and were quickly relegated to second-class citizenship.

The principal aim of Byzantium was to make Jerusalem Christian. Pilgrimages were encouraged by the provision of hospices and infirmaries; churches rose on every spot connected in one way or another with Christian traditions. The building activity that ensued was one of the causes of the country’s surprising prosperity at that time, which is evident from archaeological surveys. There were three to five times as many inhabited places in the fifth-sixth centuries CE as in any of the preceding periods.

In 610, Heraclius was crowned emperor, and many world-shaking events took place during his reign: the Persian victories, which also led to their temporary conquest of Palestine, changes within the empire, and the Muslim conquests, which deprived Byzantium of much of its Mediterranean lands. The Persian offensive had already begun in 611–and in the course of seven or eight years–the Persians conquered Antioch, the major city of the Byzantine East, Damascus and all of Syria, Palestine, Asia Minor and also Egypt.