PART IV: Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

ANCIENT HISTORY: David [999 BCE] and the Monarchial Period to the Southern Kingdom (Judah) [c. 5 87 BCE]:

Part V Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

From the Persians defeat of the Medes and taking Palestine to the years of exile terminated. (Daniel 9, Haggai 2:18-19) [541 BCE] to the Egyptians conquering Palestine to Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of the temple, to the Greeks [ 401-439 BCE] to the Roman occupation [64 BCE].

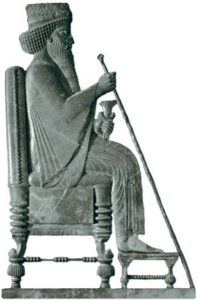

The subsequent balance of power was short-lived. In the 550s BCE the Persians revolted against the Medes and gained control of their empire, and over the next few decades annexed to it the realms of Lydia in Anatolia, Damascus, Babylonia, and Egypt, as well as consolidating their control over the Iranian plateau nearly as far as India. This vast kingdom was divided up into various satrapies and governed roughly according to the Assyrian model, but with a far lighter hand. Around this time Zoroastrianism became the predominant religion in Persia.

The Achaemenid Empire [the ancient Persian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE] took over the Levant after 539 BCE; but by the 4th century, the Achaemenids had fallen into decline. The period saw frequent rebellions by the Phoenicians against the Persians who taxed them heavily. In contrast, the Judeans were granted return from the exile by Cyrus the Great.

Pharaoh Necho tried to march through Palestine to help the survivors of the Assyrian empire to defend themselves, in their last stronghold on the Euphrates, against the newly rising empire of Babylon under Nabopolassar. Necho hoped to prevent the emergence of a Babylonian power in Mesopotamia and at the same time to achieve suzerainty over Syria and Palestine.

After the Battle of Carchemish [~609-605 BCE], Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple [597 BCE], starting the period of the Babylonian Captivity—which lasted half a century. All that lay to the west of the Euphrates was now ruled by Egypt. The picture quickly changed, however. Nebuchadrezzar was given command over the Babylonian forces in the west. Necho and his forces were completely defeated at Carchemish, and those who managed to escape were pursued and killed in the territory of Hamath. The Battle at Carchemish

—like the fall of Nineveh—changed the political picture of the Near East. A new imperial ruler had emerged: “Babylonia.”

Palestine was not a country that encouraged the creation of larger political unites. David’s kingdom represents an exception–a parenthesis in the history of the ancient Near East. The achievements of David were possible because there was a power vacuum at this time. The Hittite king-d om went out of existence around 1200 BCE. Egypt’s rule over Palestine ended sometime in the mid12th century BCE and was itself split into two kingdoms. Their successors in Palestine–the Philistines had filled the power gap for a short time, until David put an end to their political and economic hegemony. David’s kingdom, was, however, short-lived. It dissolved naturally when Solomon died.

Upon Solomon’s death at about 923 BCE, the united monarchy split into a northern kingdom, Israel, based on ten tribes and having Shechem [near the modern village of al-Balatah] as its capitol [and later Samaria c. 880 BCE], and a southern one, Judah, based on the remaining two tribes and using Jerusalem as its capital. The little southern state [Judah] was more or less limited to the tribal portions of Judah, Simean, and Benjamin, with some possessions in Edom in the east and along the coastal plain in the west.

In the north, there was the kingdom of Israel, with Shechem as its first capital–larger than Judah both in population and in size. Encompassing the portions of a majority of the tribes and the most fertile parts of the country, including the Sharon; it retained Moab and apparently Ammon, as well. The two tiny kingdoms fell into the complex political and belligerent developments of the general area and became rivals, at times enemies. Repeated uprisings and mounting intrigues in both sta- tes contributed to their final undoing. Israel experienced nine dynastic changes, involving nineteen kings, in its two-century existence. The throne of Judah was occupied by twenty kings, but the south- ern kingdom out lived the northern by about a century and a third.

The way was paved for their final destruction: one by Assyria and the other by Neo-Babylonia. Jehoiakim [King of Judah] was no match for Nebuchadnezzar, whose army entered Jerusalem in 597 and bound the rebel king with chains to carry him to Babylon. But he either died or was murdered, and his body was cast off beyond the gates of Jerusalem. The son and successor Jehoiachin was no wiser than the father. He occupied the throne three months in 597, when Nebuchadnezzar ap- peared in person at the gates of his capital [Jerusalem]. After a brief siege, the city surrendered. Jehoiachin’s uncle Zedekiah was appointed king by Nebuchadnezzar. The twenty-one-year-old Zedekiah [597-586 BCE] remained professedly loya to Nebuchadnezzar for a number of years, after which he yielded to the chronic temptation to the urge of his nationalist leaders and as usual counted on Egyptian aid. Exasperated, Nebuchadnezzar dispatched an army intent upon the destruction of Jerusalem which was (once again) accomplished.

In 586 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon–in the course of a series of wars of conquest— captured Jerusalem, destroyed the kingdom of Judah and the Jewish Temple, and—in accordance with the custom of the time–sent the conquered people into captivity in Babylonia. With the capture and destruction of Jerusalem, the kingdom of Judah went out of existence. The land was devastated, and several of the leading classes of the population were killed either in the war or after the capture of Jerusalem.

History: Second Temple Period- Return to Zion The repatriation of the Jews under Ezra’s inspired leadership, construction of the Second Temple on the site of the First Temple, and refortification of the walls of Jerusalem marked the beginning of the Second Temple period. Following a decree by the Persian King Cyrus, conqueror of the Babylonian empire [538 BCE], ~50,000 Jews set out on the first return to the Land of Israel–led by Zerubbabel–a desc endant of the House of David. Less than a century later, the second return was led by Ezra the Scribe. Over the next four centuries, the Jews lived under varying degrees of self-rule under Persian [538-333 BCE] and later Hellenistic [Ptolemaic and Seleucid] overlordship [332-142 BCE].

Xerses [486-465 BCE

The campaigns of Xenophon in 401-399 BCE illustrated how very vulnerable Persia had become to armies organized along Greek lines—Thermopylae and Marathon–with the uncontested victory at Salamis in 480 BCE. Eventually, the Greek army under Alexander the Great conquered the Levant in 333-332 BCE, and laid siege to Tyre.

Alexander did not live long enough to consolidate his realm; after his death in 323 BCE the greater share of the east eventually went to the descendants of Seleucus I Nicator. Seleucus built his capital Seleucia in 305 BCE, but the capital was later moved to Antioch in 240 BCE. Under the Seleucids, Hellenistic culture developed as a fusion of ancient Greek culture and local cultures, and the period saw notable innovations in mathematics, science and philosophy. The Seleucids founded many cities throughout the region and sponsored Greek settlement from Macedon, Athens, Euboea, Thessaly, Crete. and Aetolia.

During that period, the Greeks dominated Palestine and Israel politically, militarily, politically, and culturally. It is probable that Jesus and his father learned Greek to facilitate trade. Greek culture and ideas rapidly penetrated Palestine after the Hellenistic expansion started by Alexander the Great. Although there was a volcanic reaction to Greek influence later on, the Seleucid kings adopted the title “King of Syria”.

As part of the ancient world conquered by Alexander the Great of Greece [332 BCE], the land remained a Jewish theocracy under Syrian-based Seleucid rulers. When the Jews were prohibited from practicing Judaism and their Temple was desecrated as part of an effort to impose Greek-oriented culture and customs on the entire population, the Jews rose in revolt [166 BCE]. First led by Mattathias of the priestly Hasmonean family and then by his son Judah the Maccabee, the Jews subsequently entered Jerusalem and purified the Temple [164 BCE], events commemorated each year by the festival of Hanukkah. Between c. 140 and c. 116 BCE, the Hasmo-nean dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously in the Syrian-based Seleucid Empire, and from roughly 110 BCE, with the empire disintegrating, Judea gained further autonomy and expanded into the neighboring regions of Perea, Samaria, Idumea, Galilee, and Iturea.

After the revolt of Bar-Kokhba in 135 CE, the Romans–like the Babylonians before them–sent a large part of the Jewish population into captivity and exile. Even the historic nomenclature of the Jews was to be obliterated. Jerusalem was renamed Aelia Capitolina, and a temple to Jupiter built on the site of the destroyed Jewish Temple. The names Judea and Samaria were abolished; and the country was renamed Palestine, after the long-forgotten Philistines.

The Romans gained a strong foothold in the region in 64 BCE after permanently defeating the Seleucids and Tigranes. The Roman/Herodian Kingdom of Judea replaced the Hasmonians in 37 BCE until their incorporation of the province of Judaea in 44 CE. The first to second centuries saw the emergence of a plethora of religions and philosophical schools, all largely influenced by Rome and its Greek heritage. Neoplatonism emerged with Iamblifhus and Porphyry, Neopythagor-ianism with Apollonius of Tyana and Apamea.

The Egyptians could, and frequently did, resort to naked force in gaining their ends in Palestine… The few surviving texts from the Old Kingdom [3rd-6th Dynasties, 2688-2191 BCE] that deal with the subject do not equivocate. The most common verb used is “to smite,” referring to mortal combat. The enemy are “slaughtered,” “put to flight,” or “cowed,” and the survivors brought off to Egypt as prisoners.”

–

Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel, in Ancient Times

It was the destiny of the Holy Land, situated at the south-west end of the Fertile Crescent, to be a bridge between the two cradles of civilization, Mesopotamia (Babylonia-Assyria) and Egypt, at its extremities. It lay astride the principal land routes between the great powers of antiquity, with all the advantages and disadvantages that this involved. It was to be expected that it would be coveted by both.

-Donald B. Redford, Op cit.