PART VIII: Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Crusaders seize Gaza from the Fatimid Caliphs, returning it to Christian rule [1181 CE], to Isabella’s severe anti-Jewish leanings which influenced Ferdinand and led to the final expulsion of the Jews from Spain [1488 CE]

In a speech delivered at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II gave a grim description of the plight of the Christians of the East under the Seljuk yoke. He called on the nobility of Europe to wrest the Holy Land, the Holy City and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre–cradle of Christianity and its rightful and eternal heritage–from beleaguerment by usurping infidels who sullied them by their very presence, if not only by their deeds. Those who answered the call would be fighting a bellum sacrum [a holy war].

For the first thirty years, the disunity of the Muslim world made things easy for the invaders, who advanced speedily down the coast of Syria into Palestine, and established a chain of Latin feudal principalities, based on Antioch [1098-1268], Edessa [1098-1146], Tripoli [1102-1146], and Jerusalem [1099-1187]. However–even in this first period of success–the Crusaders were limited in the main to the coastal plains and slopes facing the Mediterranean and the Western world. The time span consisting of the 12th and 13th centuries is often called the medieval period–or the Middle Ages, in the history of Jerusalem.

In the interior–looking eastwards to the desert and Iraq–the reaction was preparing. The Seljuk princes who held Aleppo and Damascus were unable to accomplish anything of importance in that regard. In 1127, Zangi–a Turkish officer in the Seljuk service–seized Mosul [in today’s Iraq]; and in the following years, he gradually built up a powerful Muslim state in northern Mesopotamia and Syria. His son, Nur al-Din, became one of the greatest of Islamic generals and took Damascus in 1154, creating a single Muslim power in Syria and confronting the Crusaders for the first time with a recognizably formidable adversary. The issue before the two sides was now the control of Egypt, where the Fatimid caliphate was tottering towards final collapse.

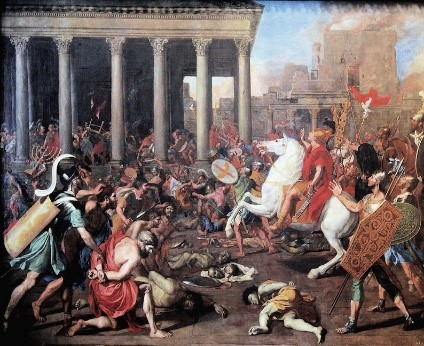

Fatimid control of Jerusalem ended when it was captured by Crusaders in July, 1099. The capture was accompanied by a massacre of almost all of the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants by the Christian knights in the name of their god. Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Godfrey of Bouillon, was elected Lord of Jerusalem on July 22, 1099, but did not assume the royal crown and died a year later. Barons offered the lordship of Jerusalem to Godfrey’s brother Baldwin, Count of Edessa, who had himself crowned by the Patriarch Daimbert on Christmas Day, 1100 in the basilica of Bethlehem.

Christian settlers from the West set about rebuilding the principal shrines associated with the life of Christ. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was ambitiously rebuilt as a great Romanesque church, and Muslim shrines on the Temple Mount; and the Dome of the Rock and the Jami Al-Aqsa were desecrated and converted for Christian purposes. It is during this period of Frankish occupation that the Military Orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar came into being. Both grew out of the need to protect and care for the great influx of pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem in the 12th century.

In Egypt, the Fatimids continued to rule until 1171, but were then replaced by Salah al-Din [Saladin], a Kurdish military leader. The change of rulers brought with it a change of religious alliance. The Fatimids had belonged to the Isma’ili branch of the Shi’is; but Salah al-Din was a Sunni; and he was able to mobilize the strength and religious fervor of Egyptian and Syrian Muslims in order to defeat the European Crusaders who had established Christian states in Palestine and on the Syrian coast at the end of the 11th century. The dynasty founded by Salah al-Din–the Ayyubids–ruled Egypt from 1169 to 1252, Syria to 1260, and part of western Arabia to 1229.

In 1173, Jerusalem was described it as a “small city full of Jacobites, Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians.” Two hundred Jews dwelt in a corner of the city under the Tower of David. In 1219, the walls of the city were razed by order of al-Mu’azzam, the Ayyubid sultan of Damascus. This rendered Jerusalem defenseless and dealt a heavy blow to the city’s status. The Kingdom of Jerusalem lasted until 1291; however, Jerusalem itself was recaptured by Salah al-Din who launched a jihad in 1187 against the Crusaders. Saladin permitted worship of all religions. By his death in 1193, he had recaptured Jerusalem and expelled the Crusaders from all but a narrow coastal strip. It was only the break-up of Saladin’s Syro-Egyptian empire into a host of small states under his successors which permitted the Crusading states to drag out an attenuated existence for another century, until the reconstitution of a Syro-Egyptian state under the Mamluks in the 13th century brought about their final extinction.

The Ayyubids destroyed the walls in expectation of ceding the city to the Crusaders as part of a peace treaty. In 1229–by treaty with Egypt’s ruler al-Kamil–Jerusalem came into the hands of Frederick II of Germany. In 1239–after a ten-year truce expired–he began to rebuild the walls; they were again demolished by an-Nasir Da’ud, the emir of Kerak, in the same year.

In 1243, Jerusalem came again under the power of the Christians; and the walls were repaired yet again. The Khwarezmian Empire took the city in 1244 and were in turn driven out by the Ayyubids in 1247. In 1260, the Mongols under Hulagu Khan engaged in raids into Palestine. It is unclear if the Mongols were ever actually in Jerusalem, since it was not seen as a settlement of strategic importance at the time.

In the middle of the 13th century, the power of the Turkish Mamluks in Cairo [Egyptian slave army] was supreme; and a new regime emerged–the Mamluk Sultanate–which ruled Egypt and Syria until 1517. In 1260, after a period of confusion following the death of the last Ayyubid, a Qipchaq Turk called Baybars became Sultan. His career in many ways forms an interesting parallel with that of Saladin. He united Muslim Syria/Palestine and Egypt into a single state, this time more permanently. He defeated the external enemies of that state, repulsing Mongol invaders from the east, and crushing all but the very last remnants of the Crusaders in Syria. The Ayyubids tried to hold on to power in Syria, but the Mongol invasion of 1260 put an end to that. In the decades after 1260 the Mamluks also worked to eliminate the remaining Crusader states in the region. The last of these was defeated with the capture of Acre in 1291.

Medieval Migdal David [Tower of David]

View and Plan of Jerusalem. A woodcut in the

Liber Chronicarum Mundi (Nuremberg 1493).

Before the taking over of Acre, Franciscan friaries were present at Acre, Sidon, Antioch, Tripoli, Jaffa, and Jerusalem. From Cyprus–where they took refuge at the end of the Latin Kingdom–the Franciscans started planning a return to Jerusalem, given the good political relations between the Christian governments and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. ~1333, the French friar Roger Guerin succeeded in buying the Cenacle [the room where the Last Supper took place] on Mount Zion and some land to build a monastery nearby for the friars. The friars–coming from any of the Order’s provinces–were present in Jerusalem, in the Cenacle, in the church of the Holy Sepulcher, and in the Basilica of the Nativity at Bethlehem.

In 1482, a visiting priest described Jerusalem as “a dwelling place of diverse nations of the world; and is–as it were–a collection of all manner of abominations”. The “abominations” he listed were Saracens, Greeks, Syrians, Jacobites, Abyssinians, Nestorians, Armenians, Gregor-ians, Maronites, Turcomans, Bedouins, Assassins, a possible Druze sect, Mamluks, and the Jews, whom he referred to “as the most cursed of all”. Another Christian pilgrim who visited Jerusalem in 1491-1492 wrote, “Christians and Jews alike in Jerusalem lived in great poverty and in conditions of great deprivation, there are not many Christians but there are many Jews, and these the Muslims persecute in various ways. Christians and Jews go about in Jerusalem in clothes considered fit only for wandering beggars.”

The monastery on Mount Zion was used by Brother Alberto da Sarteano for his papal mission for the union of the Oriental Christians: Greeks, Copts, and Ethiopians, with Rome.