PART XVI: Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

A usual day in the life of the Church of Holy Sepulchre caretakers:

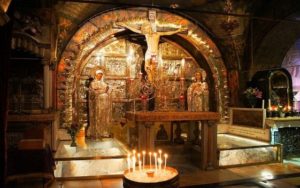

Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year—with the exception of wars occurring in or around the sacred site or for required reconstruction—the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem is a beehive of saintly activity. During the day, pilgrims from all over the Christian world flock through on guided tours. After the last tourists leave the Church in Jerusalem’s Old City at nightfall, a little-known but centuries-old tradition unfolds at one of Christianity’s holiest sites. Clerics from the three largest denominations represented in the church: Greek Orthodox, Armenian, and Roman Catholic — gather each night for special prayers reserved for the men who take care of the site where Christians believe Jesus was crucified, buried, and resurrected.

Starting at midnight, clerics and monks sing and pray for hours, their chants echoing through the cavernous chambers of the Holy Sepulcher’s darkest rooms. “The door of the church is closed, no pilgrims, no tourists, it’s very quiet,” says Father Isidoros Fakitsas, the superior of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate at the church. “It’s amazing to feel the liturgy with no people, only the monks.” Isidoros has attended the services for the past 21 years.

By agreement and of necessity, the preparations require a rigid routine. Before the first prayers of the new day, the Christian shrine is cleaned, and any maintenance work done. The clerics sweep the floors, replace oil lamps, and clean candle holders, after thousands of pilgrims have visited throughout the previous day. Occasionally a small number of devoted pilgrims help them with the cleanup and are permitted to stay and pray inside the church all night.

The early morning mass is a tradition associated with monastic life. Mostly monks and religious people want to pray not only all through the day, but also all the night, or part of the day

or part of the night. It is part of the desire to pray without ceasing because prayers to God must be given all the time, day and night, the priests and monks averre. Father Fergus Clarke, the guardian for the Franciscan community inside the Holy Sepulcher, indicates that the night prayers require a certain amount of personal sacrifice, but also bring greater spiritual fulfillment.

“That’s a wonderful vocation,” he says, … “to be able to do something like that, to know that while people are sleeping, others are praying,” he said.

The night liturgies inside the Holy Sepulcher are regulated by a consolidated tradition: The Greek-Orthodox start to celebrate mass inside Jesus’ Tomb at 12:30 a.m., before handing over to the Armenians, and then the Franciscans. The Greek Orthodox liturgy at the tomb is the longest, lasting for about three and a half hours; the Armenians then take over for an hour and a half and the Franciscans for another half hour. The night service is subject to some variations based on special religious observances. For example–on the feast of Saint Matthias on the morning of May 14–Roman Catholics lead a procession to Jesus’s tomb during the Greek Orthodox liturgy.

Sounds collided with one another that night—an unintended result. The celestial voices of Armenian priests rose from their wing of the Church as the sound of a Franciscan pipe organ came from the opposite direction. Competing for attention is nothing new in the ancient church. The three main denominations that share the church jealously guard their turf, and an air of mistrust lingers as each group makes sure no one else crosses into their space ever, even by accident.

The Tomb of Jesus and the main passages of the Holy Sepulcher are considered common spaces, but the three main religious communities each own a part of the church: The Chapel of Saint Helen, near the place where Jesus’s cross is said to have been found, belongs to the Armenians; the Greek-Orthodox Church owns the largest part of the church, including the Altar of the Calvary, where Jesus’s cross was raised; the Franciscans own the Chapel of the Crucifixion where Jesus was crucified, along with the northern part of the Church, where according to tradition Jesus appeared to his mother—a nonscriptural site.

After several centuries of Muslim rule, Jerusalem fell to the Crusaders. In 1187, however, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Jerusalem were once more in Muslim hands, after they were captured by Saladin. The Nuseibeh family was re-appointed by the Sultan to serve as the caretakers of the church. Saladin had the second front gate of the church sealed and gave its key to this family. According to the Nuseibehs, it was only during the 16th century–when Jerusalem was under Ottoman rule–that the Joudeh family was appointed as the co-guardians of the church. The Joudehs, however, claim that they had been the guardians of the church since the time of Saladin. Furthermore, the first Joudeh who was given the key to the church is said to have been a sheikh, and was not expected to do physical labor. Therefore, the Nuseibehs were appointed to unlock the gate of the church.

Today, the Joudeh family continues their job of protecting and keeping the key, while the Nuseibeh family is responsible for opening the gate to the church. As a matter of fact, there are actually two keys today. One of these is claimed to be 850-years-old; it is now broken, and no longer used. The other key–which is 500-years-old, is the only remaining functional key. That key

is kept in a small office attached to the church.

Since the end of the 19th century, a mandatory ceremony is held each year by the three main Christian denominations to renew their acknowledgement of the Muslim custodianship of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Historians differ on the roots of the arrangement. Some say Saladin most likely bestowed the guardianship upon the two families in order to assert Muslim dominance over Christianity in the city. It also had financial implications, with a tax from visitors collected at the door.

The exception to the rule of keeping the sacred keys in Muslim hands is that the custodians from each of the three main denominations are given the key for as long as they need to make a procession around the church, and then allowed to open the door after the morning liturgies, after which it is returned to the Muslim guardians. This occurs on Maundy Thursday, Orthodox Good Friday, and Holy Saturday for the Roman Catholic, the Greek Orthodox, and Armenian Apostolic Churches respectively.

Adeeb Joudeh is—by necessity of the traditional commitment of his prominent Muslim family—an early riser. After morning prayers and inspections, he appears at the Jaffa Gate to the Old City. It is 3:30 a.m. At this hour, the tension of the city seems to have melted into the darkness. The narrow alleys are eerily quiet. As Joudeh makes his way through the city’s deserted streets, his footsteps are unnaturally loud, echoing off the walls of the empty stone streets. He carries with him an ancient cast-iron key, some 500 years old. The key is 12 inches long, with a triangular metal handle and a square end and weighs half a pound.

Joudeh’s family has held the key in their protection for generations. In his house, Joudeh keeps a binder full of pictures of his grandfather and great-grandfather who once held this sacred task, and his family has kept the historic contracts bestowing upon his family this job, written on parchment and signed in golden ink. The oldest dates back to 1517.

Joudeh considers his daily ritual to be the main part of his family heritage. 53-year-old, Joudeh considers it to be a great honor for a Muslim to hold the key to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which is the most important church in Christendom.

He asserts that it is all they own as a family; and the position is an honor not only for his family; but it is an honor for all Muslims in the world. His brief case contains a set of contracts kept in plastic. It contains an ancient stamp of the Turkish sultan, dating back to the Ottoman rule of Jerusalem. He also carries an ancient cast-iron key, some 500-years-old. The key is 12 inches long, with a triangular metal handle and a square end.

In fact, he has two keys. The “new” one described above has been in use for 500 years. The old one broke after centuries of use. The older, broken, key, is 850-years-old.

“I started learning this when I was eight years old. It’s handed down from father to son,” Joudeh says. “I have been doing this for 30 years, and I feel that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is my second home.”

Although Joudeh is in charge of protecting and holding the key, another Muslim family is in charge of opening the door and allowing the faithful to enter the church. That responsibility currently falls to Wajeeh Nuseibeh. When Nuseibeh arrives at the church at 4:00 a.m., he takes the key from Joudeh, and climbs a small wooden ladder to unlock the top lock. Then he steps off the ladder to unlock the lower lock. He swings the church doors ajar, and the church is open to visitors. When nightfall hits, the two reverse the ritual, locking it up for the night.

It may seem a small thing to outsiders; but to the Nuseibeh family and Christian faithful, it is crucial. It is a model of coexistence in a city filled with tension and often hatred, leading the way in interfaith cooperation, and the protection of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as it has been for hundreds of years, owing to the wisdom of Solomon displayed by Saladin.

Wajeeh Nuseibeh never hesitates to give his differing opinion to that of the Joudeh family, which may seem small to outsiders, but is crucial to the Nuseibeh family and Christian religions is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and that was when Umar ibn Khattab took the keys of Jerusalem from Patriarch Sophronius and gave security and safety to Christians in the region. We coexist and pass peace and love, which is the real Islamic religion.” He references history from 1,400 years ago, when Umar ibn Khattab, a Muslim, made an agreement with Sophronius, a Christian, to grant the Christians right of free worship in Jerusalem.

Another of the city’s oldest Muslim families, the Nuseibehs, were entrusted with the duty of opening and closing the church doors, a task they perform to this day. It requires firm fingers: The key is a foot long and weighs half a pound. Historians differ on the roots of the arrangement. Some researchers say Saladin most likely bestowed the guardianship upon the two families in order to assert Muslim dominance over Christianity in the city. It also had financial implications, with a tax from visitors collected at the door.

Documentation, however, only goes back to the 16th century. There are dozens of “Fermans”, or royal decrees by rulers of the Ottoman empire, bestowing the key custodianship upon the Joudeh family.

Jerusalem’s Old City today houses many sites that are sacred to all three major monotheisms. It and other east Jerusalem areas were captured by Israel from Jordan in the 1967 Middle East war. Israel has since declared the entire city its undivided capital. This status is not recognized internationally and is rejected by the Palestinians who want East Jerusalem as capital of a state they hope to found someday.

“I started learning this when I was eight years old. It’s handed down from father to son,” said Joudeh. “I have been doing this for 30 years, and I feel that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is my second home.” Heading up the most recent Church renovation project is Osama Hamdan, a Palestinian Muslim architect from Jerusalem who has worked on the conservation of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim, sites across the Holy Land. He said it is a great honor to work at the church which he sees as part of his own cultural heritage.

The two Muslim families have shared this responsibility for centuries, protecting the holy site and keeping it open to the Christian faithful. It is a model of coexistence in a city filled with tension and often hatred, leading the way in interfaith cooperation, as it has been for hundreds of years, owing to the wisdom of Solomon displayed by Saladin.

A little-known devotional exercise for Latin Rite pilgrims – a daily evening procession held at 4:00 p.m. at the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This procession is not to be missed. It is a totally unique and truly fascinating liturgical experience that is hosted by the Franciscans of the Holy Land, a procession like nothing anyone has ever seen before. It takes the pilgrim on a journey through the basilica, solemnly visiting the holy sites, singing and praying with the Church’s musical handmaid, Gregorian Chant. Some of the hymns are well-known to Catholics, such as the Stabat Mater, describing the sorrows of Our Lady at the Crucifixion, composed in the thirteenth century by the Franciscan friar Giacopone da Todi. As from early Christian times, the Franciscans who act as the processional cantors are practiced singers who can read Gregorian Chant and sing the hymns and prayers from heart.

The observation of the procession is ancient, with Franciscans leading with laity following and singing as best as they can, appreciating chant as the musical art-product of the Latin Church, shaping their voices on the principle of unisonous melody. The official name of the daily procession is the Ordo Processionis Quae Hierosolymis In Basilica Sancti Sepulcri Domini Nostri Iesu Christi A Fratribus Minoribus Peragitur Custodia Terrae Sanctae. The procession consists of 14 stops at various altars to pray, reciting short prayers, versicles, antiphons, parts of psalms, canticles, and hymns. The celebrant is generally a bearded Franciscan dressed in simple surplice with a preaching stole that is interchangeable white-violet. He is accompanied by a few friars acting as his acolytes, dressed in surplices; two carrying candles and one the thurible.

Not everyone sees the Church in such a positive light, especially Protestants. Hillary Kaell reports on seven different pilgrim group’s experience in the Holy Land: four Catholic tours and three Evangelical/Baptist tours. Currently, pilgrimage to Israel/Palestine is a highly corporate enterprise, overseen by the Israel Ministry of Tourism, whose concern is (rightly) with the significant income stream pilgrimage provides to their economy, and not with the religious encounters the pilgrims crave. An American pilgrim–describing his visit to the Church in 1889–begins his description of the Holy Sepulchre by noting the divisions in the church between the Catholics and the other sects, highlighting particularly the “the schismatic Greeks; schismatic Armenians,” phrasing which certainly lacks ecumenical élan, but reflects the “jealous possessiveness” embodied in the church.

A multi-century-long battle has been raging between six Christian sects of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, a layered, winding, complex of various tombs, relics, and caverns. It is one of the most contentious sites in all Christianity. Six Christian denominations—Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, Roman Catholic, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, and Syriac Orthodox—share jurisdiction of the cavernous church and have been notoriously unable to keep themselves from throwing punches at the slightest perceived offense. Fights are not uncommon in the Church.

Warring factions can cause disastrous problems; so, when the combative holy clerics threatened the protection of one of the religion’s holiest sites, there was only one way to keep the peace: find a neutral mediator. The large ancient key that opens and locks the door of the Holy Sepulchre is shared between two Muslim families as a hereditary responsibility so that no Christian community gains full control of the church over another. Enter the two Muslim men: Wajeeh Nuseibeh and Adeeb Joudeh.

- In 1834, a stampede took place at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to celebrate the ceremony of the “Holy Fire,” which claimed hundreds of lives.

- In 1902, a dispute arose between the Franciscan and Greek Orthodox communities over the cleaning of the Chapel of the Franks’ lowest step, which resulted in 18 friars being hospitalized and some monks being imprisoned.

Following the incident, a convention was signed by the Greek patriarch, Franciscan custos, Ottoman governor, and French consul general, allowing both denominations to sweep the step in question.

- In 2002, a conflict broke out when a Coptic monk moved his chair from the agreed spot to a shaded area, which was viewed as a hostile action by the Ethiopians. As a result, eleven people were hospitalized in the ensuing scuffle.

- In 2004–during Greek Orthodox celebrations of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross–a door to the Franciscan chapel remained unclosed. The Orthodox clergymen interpreted this as an insult; and a fistfight broke out. No one was seriously hurt.

- In 2008, there were two incidents. In April, a physical altercation erupted when a Greek monk was expelled from the Holy Sepulchre by a rival group, resulting in law enforcement being summoned to the area. The irate fighters also attacked the police.

- Sunday, November 9, 2008: Greek Orthodox and Armenian worshippers traded blows Sunday in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where Christian denominations jealously protect their hold over areas of the traditional site of Jesus’ crucifixion. Dozens of worshippers, dressed in the vestments of the Greek Orthodox and Armenian denominations, traded kicks and punches, knocking down tapestries and toppling decorations at the site in Arab East Jerusalem.

The brawl erupted during the Feast of the Cross, a ceremony in which the Armenian community commemorates what it believes was the fourth century discovery of the cross upon which Jesus was crucified.

Israeli police moved into the shrine, which faithful also believe contains the tomb of Jesus, to restore order and arrested two clerics.

- April, 2021, a crush at the Mount Meron Jewish holy site killed 45 people. Authorities say they’re determined to prevent a repeat of the tragedy.

- On Saturday and Sunday, April 14 and 15, 2023, Christian worshippers thronged Jerusalem’s Old City and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to celebrate the ceremony of the “Holy Fire,” an ancient, mysterious ritual that has sparked tensions this year with the police and authorities. In the annual ceremony that has persisted for over a millennium, a flame–kindled in some miraculous way in the heart of Jesus’ tomb–is used to light the candles of fervent believers in Greek Orthodox communities near and far.

On Saturday–after hours of frantic anticipation-an Orthodox priest reached inside the dim tomb and ignited his candle. Each neighbor passed the light to another and–little by little–the darkened church was irradiated by tiny patches of light, which eventually illuminated the whole building.

Bells rang out. “Christ is risen!” the multilingual worshippers shouted. “He is risen indeed!”

Many trying to get to the church–built on the site where Christian tradition holds that Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected–were thrilled to mark the pre-Easter rite in the city where it all started. But for the second consecutive year, crowd size limits on event capacity dimmed some of the exuberance. While church leaders alleged that Israel police were unnecessarily infringing on Christians’ freedom of worship, the police indicated that restrictions on the ceremony were imposed at the request of a Greek Orthodox official for safety and security.

Angry pilgrims and clergy jostled to get through on Saturday while police struggled to hold them back, allowing only a trickle of ticketed visitors and local residents near the church. Metal barricades sealed off alleys leading to the Christian Quarter. Over 2,000 police officers swarmed the stone ramparts. Video circulating on social media showed minor scuffles between police and worshipers trying to break through the barriers. There were no reports of any injuries.

But Jerusalem’s Christian minority–mired in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and caught between Jews and Muslims–fear Israel is using the extra security measures to alter their status in the Old City, providing access to Jews while limiting the number of Christian worshippers.