PART X: Some History of Zion, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, and Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Specific history and description of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre from the 4th century CE to 1810, which is the campus of the church of today.

According to traditions dating back to the 4th century, the site upon which the Church of the Holy Sepulchre now stands was originally a place of execution for the Romans. It contains two sites considered holy in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified at a place known as Calvary or Golgotha, and Jesus’s empty tomb, which is where he was buried and resurrected. Each time the church was rebuilt, some of the antiquities salvaged from the preceding structure were used in the newer renovation. The tomb itself is enclosed by a 19th-century shrine called the Aedicule, believed to be enclosing Christ’s tomb.

According to Eusebius of Caesarea, following the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE–during the First Jewish–Roman War–Jerusalem was reduced to ruins. Undergoing several major phases of construction, what began as a place of execution and burial has been transformed into a magnificent, complex church over the centuries: first, in the 4th as the Constantinian Church of the Resurrection; next, in the 11th century, following a reconstruction; and then, in the 12th century, as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre [for the first time] following the changes made during the reign of the Crusader kings.

In 130 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian began the building of a Roman colony, the new city of Aelia Capitolina [sometime later again renamed Jerusalem], on the site. c. 135 CE, he ordered that a cave containing a rock-cut tomb be filled in to create a flat foundation for a temple dedicated to Jupiter, the goddess Aphrodite, or Venus, in order to hide the cave in which Jesus had been buried. That was during the religious reign of pagans and the violent antipathy of the Roman state. The pagan temple remained until the early 4th century CE.

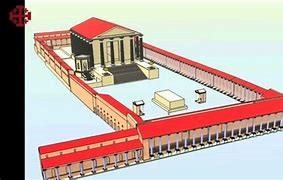

Aelia Capitolina c. 135 CE

The first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great, ordered in about 325/326 that Hadrian’s temple be replaced by a Christian church. After seeing a vision of a cross in the sky in 312–which led him to victory over his rival Maxentius on October 28, 312 CE at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge–Constantine I the Great began to favor Christianity, signed the Edict of Milan legalizing the religion, and sent his mother, Helena, to Jerusalem to look for Christ’s tomb. With the help of Bishop of Caesarea Eusebius and Bishop of Jerusalem Macarius, three crosses were found near a tomb; one which allegedly cured people of death, was presumed to be the True Cross Jesus was crucified on, leading the Romans to believe that they had found Calvary.

Constantine ordered in about 326 that the temple to Jupiter/Venus be replaced by a church. After the temple was torn down and its ruins removed, the soil was removed from the cave, revealing a rock-cut tomb that Helena and Macarius identified as the burial site of Jesus. A shrine was built on the site of the tomb Helena and Macarius had identified as that of Jesus, enclosing the rock tomb walls within its own. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, planned by the architect Zeno-bius, was built as separate constructs over the two holy sites: a rotunda called the Anas-tasis [“Resurrection”], where Helena and Macarius believed Jesus to have been buried, and; the great basilica [Martyrium], across a courtyard to the east–an enclosed colonnaded atrium, known as the Triportico–with the traditional site of Calvary in one corner. It was consecrated September 13, 335.

Ever since, the church built and rebuilt on the site has been venerated as the place where Jesus Christ died and rose again. The present author and his wife have toured through the complex of buildings and found it both confusing to take in and ornate and gaudy beyond anything they considered Christlike in simplicity. It contains a bewildering conglomeration of 30-plus chapels and worship spaces. There are no helpful signs.

The church was burned by the Persians in 614 CE, restored by Modestus [the abbot of the monastery of Theodosius, 616–626], and destroyed again by the caliph al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh about 1009 CE. After Jerusalem was captured by the Arabs in 638, it remained a Christian church, with the early Muslim rulers protecting the city’s Christian sites. But this changed on October 18, 1009, when Fatimid caliph Hakim brutally and systematically destroyed the great church–again. In wide ranging negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire in 1027-1028, an agreement was reached whereby the new Caliph Ali az-Zahir [Al-Hakim’s son] agreed to allow the rebuilding and redecoration of the Church. It was restored by the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus and Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople in 1048.

The rebuilt church site was taken from the Fatimids by the knights of the First Crusade on July 15, 1099. The Crusader chief Godfrey of Bouillon–who became the first king of Jerusalem– declared himself Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri, “Defender of the Holy Sepulchre.”

Since then, frequent repair, restoration, and remodeling, have been necessary. The exterior facade of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, on the east side of the church, was built by the Crusad-ers sometime before 1180. Subsequent centuries were not altogether kind to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It suffered from damage, desecration, neglect, and attempts at repair. A significant renovation was conducted by the Franciscans in 1555. Those renovations often did more damage than good. In recent times, a fire [1808] and an earthquake [1927] did extensive damage. The present church that the present author visited dates mainly from 1810.