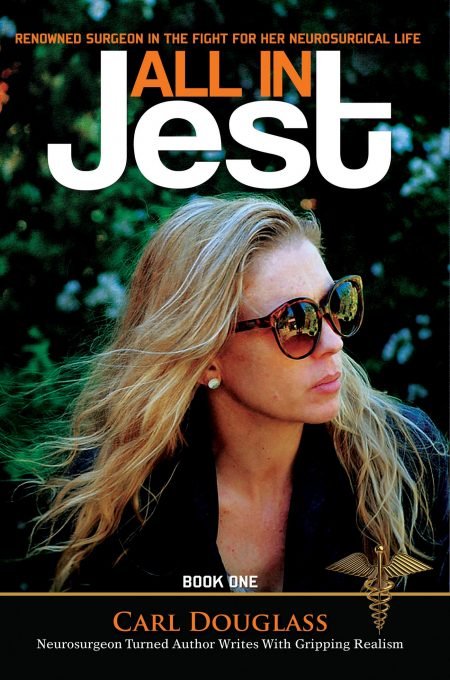

All In Jest

Chapter Two

The courtroom was stuffy–hot and full of the smell of tension.

Sybil Norcroft felt the worst she could remember, second only to that awful day five years ago that had brought her to this untenable position.

She was sure that she did not have a chance after the devastating direct examination of Pierre de Montesquiou.

It had been a stroke of the greatest genius and the best of luck imaginable for Paul Bel Geddes to have gotten the world’s acknowledged number one expert to testify for the plaintiff’s side.

The famous French Canadian had certainly skewered her defense. He had not missed a single turn of the screw.

“The prostitute,” Sybil groused to herself.

Carter Tarkington stood and walked calmly over to the witness stand. He kept back a distance of about four feet to be sure that he did not violate Judge Hendricks’s rule against approaching too close to any witness.

“Good morning, Mr. de Montesquiou.

Is that the proper form of address in your country, or are surgeons called doctor in your country?”

“I prefer the title I have earned of doctor, thank you. The same as in your country.”

“Perhaps I’m getting your country mixed up with Great Britain. They refer to surgeons as mister there, don’t they?”

“They do. But I’m Canadian. French Canadian. That is quite different, young man.”

“Yes, quite different. Let me ask you then, Dr. de Montesquiou, do you practice in the United States?”

“I am called upon to lecture all around the country, young man.

I teach neurosurgeons from all over the world, your country included.”

“My country…yes. Perhaps I wasn’t clear in phrasing my question. I’ll rephrase. Dr. de Montesquiou, are you licensed to practice in the state of Massachusetts?”

“No.”

“In New York?”

“No, I am not.”

“In New Hampshire, then?”

“No.” de Montesquiou glared at Tarkington who maintained a completely bland, almost avuncular, expression despite the incongruity in their ages.

“How about–”

“Objection. Counsel is badgering the witness.”

“Sustained. I suggest you come to the end of this line of inquiry promptly. Make your point, Mr. Tarkington.”

“Mr….I’m sorry, Dr. de Montesquiou, are you, in fact, licensed to practice in any of the fifty states of the United States of America?”

“No, but–”

“Thank you, you’ve answered my question.”

“–but.”

“Thank you. doctor. Have you ever been licensed to practice in the United States?”

“No.”

de Montesquiou glared daggers at Tarkington, aggravated by the defense attorney’s imperturbable, almost cherubic expression.

“Have you ever performed an operation in Massachusetts?”

“No.”

“In New Hampshire?”

“No.”

“Anywhere in this country?”

“No.”

“Have you ever practiced medicine, and by that I mean under the definition of the law, taken medical histories, performed physical examinations, made diagnoses, and prescribed therapy or performed procedures in the United States?”

“No.”

“Never?”

“No.”

“Not anywhere in our country?”

“No.”

“Has your actual practice of medicine, of neurosurgery been entirely limited to Eastern Canada, to the province of Quebec, to be precise?”

“It has, but–”

“Thank you, Doctor And was the entirety of your formal training obtained in your home province as well?”

“Yes, I mean, that is, I have been to all of the major clinics in the world.” de Montesquiou glared defiantly and arrogantly at his antagonist.

“Sir, my question was about your formal training.

Do you mean for us to understand that you were trained, that you were a resident, a certified trainee in, and I quote, ‘all of the major clinics in the world’?”

“That’s ridiculous. Of course not. I never–”

“Thank you, Doctor. Please, once more for the record, tell us where you received your training in neurosurgery.”

“Well, if you must have such a narrow definition of training, then I have to say Quebec. With one significant exception, that is.”

His eyes twinkled at a minor bit of one-upmanship in the offing.

“And would you tell us, please, what was that exception?”

The arrogance in de Montesquiou’s face had subtly changed to one of thoughtfulness.

He was wondering why the attorney was pressing this small exception.

“I trained in the performance of transsphenoidal surgery under the hands of the foremost professor in the world, Professor Gerard Montaigne, in Paris.”

He looked smug once again.

“Not in the United States.”

“No.”

“Were the training centers in the United States inadequate in some way?”

“Yes, indeed they were. They did not nearly measure up to the French standards. Montaigne was the pioneer.”

The looks on the jurors’ faces were hard, almost angry. de Montesquiou could have bitten his tongue.

He felt tricked into voicing his latent Gallic anti-American bias in front of a group of concrete bread and potatoes, red, white, and blue conservative American New Englanders.

Mr. Bel Geddes closed his eyes briefly in exasperation.

“Then with this extensive experience outside the United States and this great paucity of experience in our country, how is it that you can be such an expert on American medical standards, on the definitions of malpractice unique to our system, both in its medical and legal intricacies?”

“Well, young man. I mean to say that I am not an American lawyer.”

He had not meant to do so but the words ‘American lawyer’ came out with a distinct note of Frankish disdain.

The jurors frowned once more.

“But,” he hastened to regain the high ground.

“I am aware of the worldwide accepted standards of neurosurgery and most certainly of the practice of pituitary surgery, especially via the transsphenoidal route.”

“And this level of expertise is present despite a near complete lack of experience in this country, isn’t that right, Dr. de Montesquiou?”

Tarkington deliberately emphasized the foreignness of the physician’s name.

“If you wish, yes.”

“Objection.”

“I’ll withdraw the question. Let’s go on to another area.

I have heard the complaint registered against doctors that they protect their own, that they enter into a tacit conspiracy of silence when it comes to criticizing their colleagues.

How is it then that you are here testifying against one of your own, a fellow neurosurgeon, if I might use the term loosely?”

The entire courtroom chuckled briefly at the difficulty with the term “ fellow”.

“I would agree that doctors are sometimes accused of not policing their own.

That seems to be predominately a complaint heard in the U.S., incidentally.

In my country there seems to be an open exchange, even of criticisms.

At any rate, I am here to answer a higher calling, to render my judgment above such petty considerations.

I believe that I am acting in the manifest best good of neurosurgery, and more importantly, in the interests of the well-being of our sacred patients,” de Montesquiou announced grandiloquently.

He was positively beaming.

“That is certainly a lofty reason, Dr. de Montesquiou.

Would that more witnesses acted out of such high principles.

And not out of petty considerations, I believe you put it.

In that vein, Doctor, what would you consider a petty consideration?–desire to injure the reputation of a competitor, perhaps?”

“Yes, that would certainly rate as petty, and does not apply to the present case since no stretch of definition could suggest that Dr. Norcroft and I are competitors.”

“Or perhaps for purposes of male chauvinism–to put down an uppity woman?”

“That is mean and petty and beneath my dignity.

I am insulted by your insinuation, Sir.”

He looked indignant.

“Forgive me, Doctor, it was not my intention to imply such a base motive on your part, but rather to get a better feel for the level of incentive that would bring such an eminent physician as yourself to this obscure community to right a perceived wrong.

Then let us consider a final incentive,” Tarkington paused a moment, long enough to elicit a perplexed look on de Montesquiou’s imperious face, “that of money, filthy lucre.

How much filthy lucre,” his tongue caressed the words, “were you paid…exactly?”

“I am unsure, young man. I believe it was something on the order of $300 an hour. Something on that order.”

“Would that be U.S. dollars or Canadian?”

“U.S.”

“And how many hours have you donated to this mission to set the world right, Doctor?”

“Objection!”

“Sustained. Confine yourself to the evidence and forego the sarcasm if you please, counselor.”

“Sorry, your honor, in the heat of battle, I forgot myself.”

“Proceed.”

“Doctor, exactly how many hours are you being paid for? To the nearest dollar or so, how much does that amount to in total U.S. dollars?”

Tarkington’s tone dripped sarcasm, even if the words coming out of the court stenographer’s machine would appear untainted.

“I can’t say exactly, but I think I have contributed about ten hours including the deposition, viewing the radiology studies, and the video of the operation. That amounts to, let’s see–”

“Mathematics not your forte, Doctor?

Would the amount be around $3000 USD, give or take?”

“That’s about right.”

“And that is all duly recorded with your bank, Sir?”

“Well, if it is any of your business, yes, I have deposited the checks with my bank in Montreal”

“All of them?”

“Sir?”

A faint hint of alarm passed over de Montesquiou’s face.

He daintily daubed a few beads of sweat off his upper lip with a Parisian monogrammed handkerchief.

“Have you deposited all of your checks with the same bank, Dr. de Montesquiou?”

“Yes.”

“And that represents the entire payment made by Mr. Bel Geddes, the plaintiff’s attorney to you?”

“Objection.”

“Overruled.”

“What bank was that, Doctor?”

“The Bank of Montreal.”

“I have here a copy of the bank statement for your account. We subpoenaed those records. Let this sheet be entered as Defense Number l. Counselor, here is a copy for you.”

Tarkington handed Bel Geddes a sheet without looking at him.

“Just one thing, Doctor, would you read the amounts of the checks deposited to your account from Mr. Bel Geddes?”

The witness read of a series of checks and did the arithmetic for Mr. Tarkington.

“A total of $3300,” he announced, unable to keep the note of small triumph out of his voice.

“I misjudged by $300, forgive me.”

“No problem with that, Doctor.

It seems that you were perfectly accurate.

So at least we know that while your reasons for testifying were not altogether altruistic, neither were they in any way exorbitant, would that be a fair conclusion?”

“I suppose so.

I am well aware that many expert witnesses charge a good deal more.”

de Montesquiou’s face had regained its former arrogance and defiance.

“Indeed, I would have to agree with you there.

Now, it happens that I have a second bank document, also obtained by subpoena.

This one is from the Royal Bank of Canada in Ottawa. Counselor, here is your copy. I believe that should be Defense Number Two.”

“Enter it,” ordered Judge Hendricks.

“Objection to this whole line of questioning as irrelevant.

The witness has already testified that he was compensated and at a reasonable rate by our own state standards.

This amounts to badgering, your honor.” Paul Bel Geddes was on his feet.

“Overruled. I’ll allow it. But, Mr. Tarkington, get to the point promptly, will you.

We are approaching the noon hour. Will you have much more for this witness?”

“Only a couple of more questions before noon, your honor, then another hour or so this afternoon.”

“All right, get on with it.”

“Do you recognize this document, Dr. de Montesquiou?”

“Of course, what of it?” he snapped.

“Could you tell us the nature of this bank account, Doctor?”

“It is my university research account. It has nothing to do with this case. Nothing at all.”

de Montesquiou was glaring daggers at Tarkington. Intermittently, his eyes flicked briefly towards Paul Bel Geddes who never made eye contact with his witness.

“Would you be kind enough to read aloud for the jurors the entries indicating checks from Mr. Bel Geddes’s law firm.

I have taken the liberty of highlighting them for you.

And further, I have included those additional entries from Mr. Bel Geddes’s two partners, lest we leave anything out.”

Tarkington’s delivery was syrupy polite.

The witness read off a series of large checks, this time omitting the sum.

“My addition brings that to a total of $30,000.

Correct me if I’m wrong,” said Mr. Tarkington acidly.

“That seems about right,” the witness said quietly as if it were a matter of monumental indifference.

“And would you, please Sir, tell the court and these jurors the reason you received $30,000 from the law firm of Stewart, Bel Geddes, and Loughlin?”

“They were contributions to the university research,” de Montesquiou responded promptly and with assurance.

“Let’s be precise, Doctor.

The contributions were to your personal research, isn’t that right?”

“I suppose that’s right.”

“Let’s don’t suppose. Were the contributions made to your personal research fund, yes or no?”

“Yes,” he responded abruptly.

“That’s right, what of it?”

“Yes,” Mr. Tarkington said as if he were musing.

Now he was standing next to the jury box and looking directly at the jurors.

“What of it?

Perhaps we can get at the answer this way. Who controls the purse strings of that account?”

“I do.”

“You determine where the money goes, no questions asked?

At least none by the university?”

“I guess you could put it that way.”

“A simple yes or no, please.”

“Yes.”

“And the plaintiff’s attorneys just up and decided to make a very generous contribution to the research efforts of Pierre de Montesquiou, Canadian surgeon and professor, out of the goodness of their hearts, out of the clear blue sky, to coin a phrase?

Is that what you would have us believe here?”

“Believe what you like. It is true.

My research is among the most important in the world.

They seem to have recognized its value and wished to contribute.

What is wrong with that?”

“My, yes, what could be wrong with that?

I have only one further question, Dr. de Montesquiou.

Have all of these monies from Mr. Bel Geddes been reported to the Canadian tax authorities?”

“I…”

“Objection, irrelevant.”

“Sustained. Strike the question and the response. About done, Mr. Tarkington?”

“Very nearly, your honor.

I have a brief series which should not take more than ten minutes.”

“I hope not, Mr. Tarkington.

The jury deserves a punctual noon break.”

The jury looked towards the judge with relief and appreciation.

She had won them over.

“Proceed.”

“Dr. de Montesquiou, in the lengthy description of your qualifications as was brought out in your early testimony, I believe you told the jury that you were the author of one of the foremost books on the subject of transsphenoidal surgery, am I correct, Sir?”

“That is correct.

It would not be immodest to describe my book as the authority on the subject.

In all modesty, I am only the senior editor.”

He looked down, being appropriately modest.

“Ah, Dr. de Montesquiou, that is modest of you.

I understand that you wrote six or eight of the most significant chapters yourself, isn’t that right?”

“That’s right.”

He allowed himself a small smile that was not as modest as his early expression.

He glanced at the jury for their admiring gazes.

“In fact, wouldn’t it be correct to refer to your work as the ‘Bible’ on the subject, as is the common approbation given such a definitive book by the medical community?”

Tarkington was solicitous and warm.

Bel Geddes and de Montesquiou wondered where this was going.

Tarkington was establishing his opposing witness’s bona fides beyond the level that even the plaintiff’s attorney had thought would be taken as overkill when he had puffed the doctor’s standing in the medical community to the jury in his early questions of the French Canadian.

The last thing in the world Bel Geddes wanted to do was to interfere with the golden flow of communication between his star witness and the jury with an ill-timed objection.

de Montesquiou surveyed the jury.

Rural bumpkins, the lot of them, including the country lawyer facing him.

He decided to give them a little leavening education.

“It is perhaps an overstatement to think of my book as the ‘Bible’, Counselor.

I heard it described once in a way that seems more accurate and to the point, medically speaking. It was compared to the works of Galen, and all books afterwards should be known as ‘Galenic Operas’.

That was not my description, but perhaps it fits.”

“Forgive my ignorance regarding classical matters, Doctor. I got my undergraduate education at CUNY, night school, actually.

Perhaps some of the jury could use a refresher about Galen and whatever a Galenic Opera is.”

“Happy to oblige,” de Montesquiou condescended.

His quick glance assured him that the jury was suitably impressed with his erudition.

“The point of reference comparison between my book and the works of Galen is that Galen’s works were considered so authoritative and timeless that they were memorized.

Even further, they were rendered into verse; so, the common students and physicians could better learn them.

Finally, over the nearly 400 years of their primacy, Galen’s utterances were put to music and presented as operas to preserve their wisdom and to encourage their promulgation throughout the civilized world.”

“And,” thought Sybil, listening to the man’s flagrant self-aggrandizement, “Galen’s original works, and especially the Galenic Operas, were the very antithesis of science, the triumph of uninformed authoritarianism and consensus over the experimental method.”

She longed to launch a debate, but knew she simply had to sit and listen to the Frenchman’s drivel.

What Carter’s reason for pursuing this line of questioning was, she could not fathom.

“Thank you, Dr. de Montesquiou.

I think I truly see the level at which your book should be accepted.

I am sure the jury has a firm concept and will bear the importance of your book in mind as they deliberate.

“I have no further questions, your honor.”

“Mr. Bel Geddes?”

“None, your honor.”

Who was he to detract from that soaring paean?

“We are ready for lunch if your honor deems it an appropriate cutoff point,” volunteered Carter Tarkington.

“Until two o’clock,” Judge Hendricks ordered.

True to his word, Darryl Hankin waited patiently until the patient could be repositioned for the closure.

His prepaid tee time at the Westhaven Country Club had come and gone, but he did not complain. Sybil Norcroft surveyed the damaged body of Brendan McNeely.

Her eyes took in a large gaping leg wound and two irregular, asymmetrical neck wounds, far larger than a proper carotid surgery would have required.

The scars would be dreadful, if the handsome young man lived long enough to have scars.

She Betadine swabbed all the wounds herself and redraped them so that the fields again took on the semblance of a surgical operation instead of looking like a battlefield casualty. Sybil relaxed enough to emit a heavy sigh.

“My sentiments as well,” said Dr. Hankin in all sobriety.

Sybil was angry. She inwardly cursed herself.

The disreputable quality of the incisions was the last straw.

She had no one to blame but herself.

Dr. Hankin had been working under abominable conditions when he did the neck and leg procedures.

It was a wonder that the openings were as neat as they were.

She wanted to rage at him, at the anesthesiologist, at the patient, even.

But she directed her wrath at the one responsible, the captain of the ship.

She silently ran down her entire rather extensive list of expletives, applying all of them to herself.

“3-0 chromic catgut,” she requested and held out her hand to receive the needle holder.

Sybil closed the right side neck wound while Dr. Hankin closed the leg wound.

They worked together to close the left side of the neck.

When the last 5-0 monofilament nylon skin suture was in place, Sybil looked over the anesthesia screen at Howard Derriel who was busily adjusting a clogged IV line.

“Howard,” she said, “you can shut off the gas now, we’re done up here.”

“I hate to say it, but I haven’t been giving him any anesthetic for the last hour, Sybil.”

The anesthesiologist’s flatly delivered statement was like a stinging backhand facial slap to the exhausted and tense woman neurosurgeon.

She could not escape the import of that observation. If luck were on her side, Brendan would be awake by now.

It is better to be lucky than good, Sybil thought, but right now she felt neither lucky nor like a good surgeon.

She sagged a little.

“Let’s get him straight to the NICU, no need to stopover in the PAR. Okay with you, Dr. Norcroft?” asked Howard.

“Whatever,” Sybil replied listlessly.

She felt thoroughly defeated.

The worst was yet to come.

She had to face the family.

How she wished for that particular cup to be taken from her.

The cortege of grim faced doctors and nurses wheeled the gurney with its inert occupant down the hall to the NICU.

Brendan’s family was waiting in front of the intensive unit door, having been directed there by the risk control officer of the hospital, but having been given no insight into their son, grandson, and brother’s condition.

“Dr. Norcroft,” cried Brendan’s distraught mother, “what’s going on? How’s my boy?”

“Let me get him settled in his ICU bed, and I’ll be right back out to answer your questions and tell you all about it,” Dr. Norcroft said gently but firmly, and edged the gurney past the anxiously onlooking family.

“Don’t envy you this one, Sybil. I wouldn’t be a neurosurgeon for all the tea in China.

ENT’s the thing for me.

Nobody ever dies.

I can’t remember the last disaster I even heard of.

I hear this is the crème de la crème of the valley out there.

Good luck,” Dr. Hankin said.

He gave a little wave as he turned and headed for the rear entrance of the NICU.

“Thanks. Thanks for all the help, Darryl.

You were great. I owe you,” Sybil called after him.

The confrontation with the family was as grim as Sybil might have expected it to be. Although medical laymen, they were neither unsophisticated nor naive.

Only fools would have missed the fact that the situation was grave, and these people were no fools.

If it ever occurred to Sybil Norcroft to be less than candid, she knew that now was not the time nor was this the place.

“Hello,” she said as soon as she entered the conference room where the risk officer had assembled the family. “For those of you who don’t know me, I am Dr. Norcroft, Sybil Norcroft.”

“What’s going on, Doctor?” asked Carl McNeely, Brendan’s father, and the tacitly acknowledged family spokesman.

He was the well-known chairman of the board of Computer Exporters International. Brendan’s mother sat white faced and white knuckled in a corner easy chair.

“The direct answer to that question, Mr. McNeely, is that I’m not altogether sure, and it will take time, maybe even a day or two to be sure.

Let me tell you about today’s happenings, starting from the beginning and bring you up to speed about where we are right now.”

“Happenings?” whispered several of the family members in the background.

Sybil started from the very beginning, about finding the galactorrhea and how embarrassed Brendan had been about his milk production, about the laboratory findings, and then she launched into a detailed description of the course of the operation not sparing herself, even the smallest jot or tittle.

She praised Dr. Hankin’s role for coming in to assist in the emergency situation, explained the decision not to take the gravely ill young man to the post anesthetic recovery room, and his current status in the NICU.

When she finished her narrative, she asked, “Any questions?”

“A bundle,” said Carl McNeely.

His face was a mix of determined anger and fear. “I’ll settle for one right now. Is my son going to live, Dr. Norcroft?”

“I honestly don’t know, Mr. McNeely.

He has failed to wake up, and usually people do by this time after an operation of this kind and the type of anesthetic he received.

He could die.

It is premature to speculate at this point.

I can be definitive in forty-eight hours.”

“Then I have a second question.

Maybe it, too, is premature.

But here goes.

If Brendan pulls through, will he have his faculties?

Do you expect him to function normally?”

“That’s another fundamentally good question, and unfortunately, I still can’t give you a real answer yet.

Let’s plan to meet each morning somewhere between six thirty and seven when I make my rounds.

I will give you the latest then.

I’m sorry about this turn of events. I would give anything if this problem had not occurred, but it did; and now we have to deal with the situation as it is.

I’ll be with him as much as it will help,” Sybil concluded with a note of earnestness that expressed human concern, admitted responsibility, but did not suggest fault.

“I am going to ask another neurosurgeon to consult, Doctor.”

It was expressed with such matter of fact resolve that Sybil knew that her problems had just begun.

Brendan McNeely did not awaken by rounds on the second day post-op.

In the interim he had demonstrated reactivity to noxious stimuli only on his left side and over the course of twelve hours had become progressively less reactive, decorticate, decerebrate, and finally was responsive only to respiratory system stimuli.

When Sybil left his bedside the previous night, his EEG had erratic slow giant waves, and his pupils were fixed and dilated.

His only response had been a slight cough when the endotracheal tube was moved. On morning rounds, a repeat EEG was a flat line, more sophisticated brainstem electrical tests were similarly unresponsive; and Brendan did not respond to either cold or hot water placed in his ears. There were no brainstem reflexes, and he did not flinch in the slightest at even deep painful stimuli.

Sybil had been dreading this moment.

She knew she had to face the family, but would have given anything just to have been swallowed up by the earth at that moment.

Before going out to the quiet conference room, Sybil wrote her concluding progress note and last set of orders.

She called to the charge nurse, “Angie, can you get the medical examiner’s office for me. Brendan is gone.

I need to report it.”

Silent tears were streaming down Angie’s face as she handed Dr. Norcroft the telephone. Angie and Brendan had been friends, had even dated a few times.

There was not a person in the NICU who did not know and like him, and there was not a dry eye anywhere.

Some of the eyes quietly shone recriminations at the neurosurgeon.

“Hello,” Sybil said into the receiver, “this is Dr. Sybil Norcroft at Joseph Noble Memorial Hospital. May I ask with whom I am speaking?”

She wrote in the progress note, “Douglas Stringham, ME aide.”

“Mr. Stringham, we have just had a death here in the neuro intensive care unit.

The deceased’s name is Brendan McNeely, middle name Alfred. Yes, Sir, that’s B-r-e-n-d-a-n A-l-f-r-e-d M-c-N-e-e-l-y,” she spelled for the aide, then gave Brendan’s vital statistics, age, date of birth, diagnosis, and cause of death–exsanguination during surgery.

“Is it standard to do an autopsy, Mr. Stringham, in cases like this?”

Sybil listened to the answer as did Angie on the other line. Half a dozen NICU workers had gathered around to listen to Sybil’s end of the telephone conversation.

Among them were the orderly, Jasper Heaton, who looked at the pale neurosurgeon’s face with unfeigned sympathy, and Heather Larkin, RN, CNRN who was less kindly disposed.

She was inclined to think that the arrogant Dr. Norcroft might just have gotten herself into trouble by not using an ENT assistant like everyone else, and the cost was a dead boy, not just any dead boy, but one of their own.

Her teeth were grimly set on edge.

“I see,” Sybil responded.

“I’m sure you are terribly busy there, and I sympathize with your department, but it’s still your job to do autopsies, and I want an autopsy on this patient.

I want to know why he bled to death.”

Dr. Norcroft listened with mounting anger showing in her face.

She was becoming flushed.

“I really don’t care what you want, Mr…

I demand an autopsy. If that is a problem, you have the medical examiner himself give me a call.

I’m in the book.

There will be hell to pay if you don’t do a postmortem.

I expect special attention to the pituitary fossa and the carotids.

Do I make myself clear, mister?!”

Sybil listened for a moment longer, shook her head in disgruntlement at whatever was being said, and concluded with a terse, “Good day to you, as well, Sir.

I will be expecting a phone call in the next twenty-four hours.”

She put down the receiver and muttered, “Pipsqueak.”

The confrontation with Brendan’s family was less emotional than Sybil had anticipated. The McNeely’s were made of stern stuff and had watched Brendan’s steady deterioration over the past two days.

The formal declaration of death came neither as a surprise nor a shock.

They listened with patient resignation as Dr. Norcroft gave them the unembroidered details of the findings.

“He is brain dead, by every criterion.

There is absolutely no hope of recovery. His heart keeps beating, and his lungs keep inflating and deflating only because of life support machines.

When I turn them off, all of that will stop in a matter of minutes.

I am dreadfully sorry about this turn of events.

I cared for Brendan personally and feel some of your loss.

We did everything we could, but medical science is just not up to the problem or combination of problems we encountered with your son.

He will be taken to the medical examiner’s office where they will do an autopsy.

Then your designated funeral home will receive him. Can I answer any questions?”

Brendan’s mother, her face swollen and puffy from crying, looked bewildered and seemed to be struggling to understand as if she had been spoken to in Chinese.

“I can’t understand this, Doctor.

He was so young and healthy.

What happened?

Why is my boy, my only son, dead?

I want to know that.

This was supposed to be a safe operation.

You are supposed to be the best.

How can this be?”

The questions were emotionally cathartic, rhetorical.

The distraught woman did not expect answers.

She knew in her heart that there were none.

Or, at least, that none would be forthcoming right then.

Sybil reached out and rested her hand on the forlorn woman’s shoulder.

Mrs. McNeely recoiled from Sybil’s touch, almost as if she had been injured.

A look of the purest hate gleamed out of her reddened eyes.

Sybil took an involuntary step back towards the door.

“Doctor,” said Carl McNeely in a hoarse magisterial voice, “you have not heard the last of this. Not by a long shot.”

His look of hatred was mingled with a clenching of his jaw muscles that bespoke austere determination.

The family’s consulting neurosurgeon, Blackman Schwartz, agreed with Dr. Norcroft’s diagnosis and found no fault with her NICU treatment.

Together they started to remove the life supports, a silent, businesslike, and sad set of tasks.

As the two neurosurgeons moved the patient’s body in the course of their ministrations, one of Brendan’s great toes moved upward in a spastic dorsiflexion. and his leg stiffened slightly and momentarily at the knee.

“Peripheral reflex, doesn’t change the diagnosis,” observed Dr. Schwartz and deflated the balloon of the endotracheal tube.

“Stop!” cried the voice of Heather Larkin.

The certified neurosurgical registered nurse put her hand on Dr. Schwartz’s forearm to prevent him from extracting the breathing tube.

“He moved; he isn’t dead!

Not quite anyway.

It’s too soon He isn’t dead!”

She was angry.

She looked at Sybil Norcroft with undisguised hostility.

Sybil ignored the provocation and maintained a civil tone and a calm expression.

“Yes he is, Heather.

That was a transient peripheral reflex.

You know that his brainstem reflexes are gone, and his EEG is isotonic, completely flat.

We ran a strip for five minutes without a spike. Take it easy, Heather,

it’s hard on all of us.”

“It’s Mrs. Larkin, Doctor.

And you don’t need to patronize me.

I can see.

This man’s not dead.

You can’t wait to put him in the ground, so your precious reputation will be saved.

There’s no hurry.

We can repeat the EEG.

If you go ahead and undo the rest of his supports, I am going straight to Michael Strong, the administrator.

Don’t think I won’t.”

Now, Sybil was provoked.

She could not afford to have her judgment nor her authority challenged in her own NICU. Her voice was quiet, cold, and hard.

“Take your hand off Dr. Schwartz.

Let’s get one thing straight here and now and for henceforth.

I am the doctor, the expert.

You are the nurse, and for all your extra training to get the neurosurgical certification, you are still the nurse.

Our roles are established by laws.

Now I am going to do my work, and you are not going to interfere, or I am going to Michael Strong.

Understand?

Now go out and get me someone who can maintain his or her objectivity–a professional.”

Sybil had not intended to be insulting, just to let Heather know where the bear slept. Heather, already angry and emotionally at the end of her tether, clenched her fists, held her tongue, and did a smart about face and left.

She went directly to the administrator’s office.

Mr. Strong listened to the excited senior nurse at first with a patronizing indifference, then upon learning who the patient and his family were in the community, grew deeply concerned.

He put aside his papers for the third time that day and followed the nurse down the two flights of stairs to the NICU.

They were too late to change anything.

The tubes and lines were separated from their lifeline machinery.

An EEG and an electrocardiogram were running, and both were dead flat.

It was over.

Michael Strong shrugged his shoulders without saying anything.

He was loathe to get involved in medical matters unless they bubbled up to the administrative surface.

So far as he could see, the matter was closed and could not be changed.

Not so with Heather Larkin.

She was incensed.

Her pleas, her professional opinion, her demands, had gone entirely unheeded.

“You think you’re God, Dr. Norcroft.

I’ve seen that sign on your desk. GOD.

But even you can’t get away with just taking away the life supports of someone who isn’t already dead.

Only God can make that kind of a decision.

You are not above God, and you are not above the law. I am going to report you!”

Her voice had become shrewish and shrill.

She heeled about and left hurriedly before she said anything more.

Angie took over her duties when Heather left the NICU early.

Shortly, Sybil Norcroft was left alone with the body of her patient, Brendan McNeely. When she was sure that no one would come in, Sybil allowed tears to cascade down her cheeks, rivulets of hot brine that scalded and angered her.

Sybil had endured the insults of her medical school classmates, the demands of unreasonable taskmasters during her residency, the unfair competition in practice that had made her work twice as hard as any man to gain her position, the neurological injuries and deaths to patients that accompanied her chosen field of endeavor; and she had never shed a tear.

She had never folded and acted like a silly, petulant, emotional woman.

She had lost patients before and handled the anguish with stoicism.

Now, she was personally involved, threatened, and a young man about whom she cared, more than she had realized, was dead.

His light had prematurely been snuffed out.

It was not fair.

Life was not fair.

And no one cared a whit about how she felt, she who always had to be so tough, the Snow Queen.

She knew they called her that, and she resented it deeply.

And now the irrepressible tears would not stop coming, no matter how hard

Sybil fought them.

A great barrier had burst open.

At two o’clock on the dot, Judge Kendricks rapped her bench with her gavel. “Everyone here and in his or her place, bailiff?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“Let us proceed, Mr. Tarkington. I’m counting on you to finish the cross on this witness this afternoon.”

‘Thank you, your honor. I believe we can finish before five. Dr. de Montesquiou, I’d like first to ask you if you have seen the video tape of this case?”

“Yes.”

“Just briefly, what did you see?

Let’s cut to the chase and consider the point of bleeding.

No use boring the jury with the preliminaries.”

“I saw an eleven blade knife, and incidentally, I never use a sharp pointed knife for that opening cut into the dura.”

“Was that incision pretty much in the midline, not out lateral in the area of the carotid artery?”

“That’s right.

The incision was too deep. It cut into an aneurysm, and then there was the most terrible hemorrhage.”

“You saw the aneurysm, Sir?”

“Not directly. It had to be there under the dura waiting for the disaster of an ill placed incision.”

“Let me be clear on this, Sir.

Did you or did you not see the aneurysm itself?”

“No. I did not, but–”

“Thank you, Dr. de Montesquiou.

One last question about the video, just a technicality, really.

You said that you spent a lot of time reviewing the video tape, even charged for it, is that right?”

“Indeed. I was very thorough.”

The arrogance of the man was never more evident.

His plump patrician face with its pampered Van Dyke beard reflected his superiority.

“My question, just for the record, as I said, just a technicality, how long was the tape, the tape you looked at.

That was a copy of the original, right?

Sent to you by Mr. Bel Geddes?”

“I reviewed the tape of this operation.

It was provided to me by Mr. Bel Geddes, or someone in his office, I can’t say that exactly. It was precisely 39 minutes long.”

He smiled.

“I thought you might ask for such a detail; so, I made a note of it.”

He looked pleased with himself, like the young cat who has just caught his first mouse.

In the intellectual game being played out in that courtroom, he had just scored a small bit of one-upmanship.

The attorney had not been able to trap him into any kind of admission of doing a shoddy or incomplete job.

de Montesquiou gave a look of satisfaction with his performance at this juncture to the intently observant jury.

Carter Tarkington paused briefly to make a quick note on the yellow pad lying on the attorney’s podium.

“Now I’d like to explore the opinions you expressed about the diagnosis and surgery of Mr. McNeely.

Is it not a reasonable assumption that a person, no, that the deceased in this case, had a prolactin secreting tumor if he had galactorrhea, an elevated serum prolactin level, a thinned sellar floor, and CT evidence of a pituitary tumor?”

Dr. de Montesquiou turned to face the jurors, to talk to them.

“Stated that way, that would be a reasonable conclusion, but…”

“Thank you, Doctor. Now…”

“I have not finished the answer to your question, and the impression…”

“Yes you have, Doctor. The answer was quite adequate.”

“Objection. Your honor, the doctor needs to be able to answer the question and not to be cut off when Mr. Tarkington has what he wants.

The witness is an expert, and as such, should be given the courtesy of allowing him to explain.”

“I agree. Objection sustained.

You may answer the question, Dr. de Montesquiou.

Take your time.”

“Thank you, your honor.

As I was trying to say, phrased as the defense counsel put it, the diagnosis would be fairly clear cut.

A layman would be able to glean the diagnosis out of a medical cookbook.

But professionals need to proceed with more care.

First of all, in this case, no one but Dr. Norcroft ever saw the milk production that she characterized as galactorrhea.

We have only her word that it was ever present.

Secondly, the prolactin blood level of 75 was too low to be sure that it was a tumor, and it was more likely from ingestion of drugs. Lastly, I am not at all sure that what we are looking at on the CT is a tumor, that the sellar floor is actually and focally thinned.

And, in addition, I believe there is an aneurysm demonstrated on the CT.

To my way of thinking, the diagnostic workup was flawed, the decision to operate was precipitous, and the operation was performed well below the standard of care for neurosurgeons.

The worldwide standards were all violated.”

“And are you free of bias, Dr. de Montesquiou, you with your $300 an hour salary and your $30,000 neatly tucked away in a research account controlled solely by yourself?”

“I believe that I am.”

“Then with that admirable objectivity of yours, Sir, can you not consider that a reasonable professional would conclude differently from your own judgment that the elevated prolactin, the history and the finding of galactorrhea on her own examination, and the suggestive imaging evidence that there was a surgically removable tumor?”

“No, Sir. I am the world’s premier transsphenoidal surgeon.

I can say that in all modesty and without fear of contradiction.

I say there was no tumor.

The operation should not have been done and was done badly.

And that is all there is to it!”

“And ‘thus spake Ozymandius, king of kings, look on my works ye mighty and despair!’” said the defense attorney with a theatrical flourish.

“Objection! Your honor, I protest!” Bel Geddes was shouting.

“No need to raise your voice, counsel.

And you, Mr. Tarkington, shame on you.

You know better than that.

The jurors will ignore that last remark, and it will be stricken from the record.

Don’t let it happen again, Mr. Tarkington.”

“I stand chastened, your honor.”

He did not look chastened.

The judge leveled a look at the defense attorney but forbore to say more.

“Dr. de Montesquiou, what was the cause of this hemorrhagic accident in surgery, then?”

“The simplest response to that question is that Dr. Norcroft cut an aneurysm.

That’s the long and short of it.

Here, let me show you on the CT scan.”

“Be my guest.”

The doctor found the film he wanted and put it on the courtroom view box.

He pointed to a thickening above the sella.

He smiled indulgently at the jury.

“No possibility that the carotid artery was located anomalously, or that there was a major arterial branch crossing the floor of the sella where it should not have been, or even that Dr. Norcroft extended her incision too far laterally?”

“We never say never or impossible in medicine, counselor, but the first 999 possibilities are that Dr. Norcroft missed an aneurysm and the one out of a million is any of the other causes,” de Montesquiou pontificated.

“I might add that I have never seen nor heard of such a case in all my years of a so-called anomalous carotid; that’s the excuse of the careless surgeon.”

“I’m not sure that the numbering system adds up, but I think I understand your message. What about the possibility of Dr. Norcroft having cut too far out and nicking the carotid, Doctor?

Would that be in the one-in-a-million category?”

Sybil Norcroft winced slightly wondering where this line of questioning was leading since it did not tend to put her in the best light.

She kept a poker face.

“I hate to admit this, but I think that’s correct.

I am certain beyond any reasonable doubt–way beyond, in fact–that Dr. Norcroft never got a chance to make her incision too far lateral.

She ran into the aneurysm and broke a hole in the dike.

Even if it would put Dr. Norcroft in a better light than she deserves, I’d have to say that the chances are less than one in a million that she did anything other than cut into an aneurysm as the cause of the bleeding and death of this unfortunate young gentleman.”

The eminent doctor-professor had a look of supreme confidence tinged with sadness at having to criticize a colleague.

“You mention that it is better than she deserves to make a harsh criticism of her.

I take it that you are aware of some long dismal history of improper conduct on Dr. Norcroft’s part, or you know some egregious bit of conduct in this case that you have not yet shared with us about her that would make Dr. Norcroft unworthy of even the consideration of anything but a litany of evils, of which you have reluctantly selected the worst as the only plausible consideration.

Since you are, by your own statement, objective, and not testifying for filthy lucre, we can assume that you are nothing of an advocate for the plaintiff’s side in so saying, can we not?”

“I, …well, I should say, I suppose that I may have overstated myself a fraction.”

“Ah, down to cases. Dr. de Montesquiou, do you know of anything negative concerning Dr. Norcroft’s record?”

“Well, no.”

“Do you know anything about her beyond the case before this court?”

“Well, yes, I know that Dr. Norcroft is very well thought of in neurosurgery circles for her work in pituitary tumors with lateral extensions and other skull base neoplasms.

She is probably the foremost woman neurosurgeon in the world, despite her relative youth.”

The answer was delivered with a Gallic flourish bordering on the romantic.

He intended his praise to offset any personal animus or lack of deference to the fair sex of which he may have been suspected.

“I don’t know how they do it in the courts where you come from, Doctor, but I’ll ask you. Do you think Dr. Norcroft is deserving of a trial?

Of a fair trial?

Or should we just say ‘off with her head’ after we hear what you think about the situation?

You being so objective and all.”

“Objection! I object.

This is entirely uncalled for.

This is an eminent physician deserving of respect here.

I object to this whole line of questioning!” shouted Paul Bel Geddes.

He was not participating in theatrics.

He was genuinely angry.

His face was livid.

“Don’t object any more, counselor.

And do not ever again raise your voice in my court room.

Do we have an understanding?”

Judge Hendricks spoke quietly and civilly to Mr. Bel Geddes, but she was looking intently at Carter Tarkington.

“Yes, your honor,” responded Bel Geddes.

Tarkington and Dr. Norcroft knew that the defense attorney’s turn was close at hand.

“I am out of patience with you, Mr. Tarkington.

First of all, we will strike your last question and the witness’s response.

I admonish the jury to ignore that question and answer as well as not being either proper or relevant.

Ordinarily I would call a sidebar discussion or a meeting in chambers, but I believe the jury should hear this. Mr. Tarkington.

If I hear another such breach of courtroom etiquette, I will hold you in contempt. Do you have any questions, Sir?”

“No, your honor.”

Tarkington was stone-faced.

“Then proceed with caution,” the judge ordered.

“I have no more questions for this witness, your honor,” Tarkington said unrepentantly.

“Call your next witness, Mr. Bel Geddes.”

“The plaintiff calls Douglas Stringham.”

The witness was sworn.

“State your occupation, Mr. Stringham.”

“I am an aide for the Caldwell County Medical Examiner’s office.”

“And were you serving in that capacity on the morning of September 8, 2001?

“Yes, Sir.”

Stringham was nervous.

He looked about frequently, shifting his eyes from the plaintiff’s table, to that of the defense, and to the judge’s bench on the dais.

He did not establish or maintain eye contact with the jurors.

Between answers, he chewed his nails.

“Did the name of the deceased, Brendan McNeely, come to your attention on that day, Mr. Stringham?”

“Yeah, it did.

It sure did.”

“Please describe for the court what impressed you to remember the name.”

“Okay. Well, see, like I got this call.

It was early, I remember that. A lady doctor, some kinda surgeon, called the office.

She like reported that there had been a death. This guy, this McNeely guy, had died that morning.

She said that he had had like a bleeding spell in the OR.

That’s why he died, she said.

Wasn’t no big deal, she said.

Just like happened, you know, like that kinda sh–, uh, stuff happens in surgery. Who was I to know? Like who was I to question a brain surgeon?”

“What did you say?

Do you remember?”

“You betcha.

I went right by the book.

I go, ‘do you want a autopsy, Doctor?’

She goes, ‘No, this is like just a routine thing, you know, part of the deceased’s disease, kinda thing we expect’.

That sorta explanation.

I remember goin’, ‘but don’t you think like we oughta find out why there was bleedin’?

She goes, ‘it’s just routine.

Besides the family don’t want no autopsy.

Some kinda like religious thing,’ I think she mentioned.”

“Then what did you do?”

“I took her word. She’s a big doctor an all, you know.

I just logged in the case and like asked to talk to the nurse.

But the doc had already hung up.

I hadda call back, like I wasn’t busy nor nothin’.

Doc was snotty about it, real curt.

Like you know?”

“I understand.

Thank you. I have no further questions.

Sybil passed a note to Tarkington that read, “Complete fabrication.

Opposite is true. He made all of that up out of whole cloth.”

Tarkington glanced at the note but made no acknowledgment that he had seen it.

“Good morning, Mr. Stringham,” he said affably.

“Mornin’,” the witness responded warily.

“It is ‘Mr.’ isn’t it?

I mean, you’re not one of the doctors, are you?”

“No, I ain’t.”

“Are you responsible for making the decisions at the medical examiner’s office?”

“No.”

“Who makes the decision about whether or not an autopsy is done by the medical examiner?”

“One of the doctors.”

“Then they review each of the cases called in?”

“Sorta.”

“What does ‘sorta’ mean?”

“Well, it’s purty busy in that place.

Like, usually what happens is that the aides give a list of cases for the docs to decide on. Then one of the docs will go, ‘Yeah, do it or no, don’t do it.’”

“And did you put Mr. McNeely’s name on that list?”

“I can’t remember that.

Maybe yes, maybe no. Like, man, that was like five years ago, you know.”

“Yes, now that you mention it, it does seem like a long time ago.

Do you have a pretty good memory, Mr. Stringham? Would you say it was better than average?”

“I like to think so. Yeah.”

He grinned. His teeth were in need of straightening.

A front incisor and a molar from each side were missing.

Sybil was feeling hostility.

It was too bad that the inventor of the tooth brush had not called it the ‘teeth brush’.

Maybe Mr. Stringham’s smile would have fared better, she thought.

“It seems to me pretty remarkable that you can remember this one case from out of the past, from five years in the past.

I guess you don’t have that many cases, is that right?

Or maybe there was something special about this case that made it stand out in your mind, in your memory?”

“There was something special.

It involved a swell, one of the RBs from out in the valley.”

“‘RB’? I’m not familiar with the term.

Please enlighten the court.”

“You know.”

“No, Mr. Stringham, I really don’t.”

Stringham was squirming, looking nervously at the judge and over at the jury box.

He sought but did not find help from the defense table.

“Uh, it means rich, ‘R’ for rich. You know.”

“I thought it was ‘RB’?”

Stringham was obviously uncomfortable.

He was blushing. “Rich…Bad guys, somethin’ like that.

Just a expression, Jeez.”

“We’ll let it drop.

I forgot now, how many people did you deal with in a day?

Give us an estimate of how many calls, how many autopsies, how many visits to the office you handle?”

“I can’t remember ‘zactly.”

“Just an estimate, Mr. Stringham.

Your best try, please.”

“Must be like fifty a day, somewheres near there.”

“We’ve done a little investigating on our own.

Would it surprise you to learn that your office averages 250 calls, just the telephone calls, every day, six days a week, twelve months a year?

“If you say so.”

“Not me.

Your office says so.

Now, by my calculations, that is roughly 7500 calls a month, give or take, or about 90,000 a year. That seem right to you?”

“Yeah, maybe.

We’re pretty busy, all right.

Like, I work real hard, I tell you.”

“How long did you work at the ME’s office before September 8, 2001, Mr. Stringham?

“Objection, irrelevant.”

“I was wondering myself, Mr. Tarkington.

Is this leading somewhere?”

“Indeed, your honor.

Just a few more questions, and I will make that amply clear.”

“Proceed, but don’t try my patience.”

“Did you understand the question?”

“I don’t remember what you said.”

“Would the court recorder please read back the question?”

He did.

“I hired on…let’s see, I was eighteen.

That’s–let’s see–five years, yeah, like five years.”

The witness smiled at his feat of memory and turned so that the jury could witness his accomplishment.

“How long have you worked with the ME’s office since?”

“Seven years and three months.”

This time his answer was prompt and crisp.

He was very pleased with himself.

“How many of those 250 calls a day that come into the office do you handle by yourself?”

“There’s four of us aides, about half enough, I say.

So I handle, let’s see…”

It was a tough math problem, Doug Stringham had never been that good at story problems.

“About 62 or 63 calls, 63 cases a day if you do your share.”

“I do more’n my share,” Stringham blurted asserting his industriousness of which he was justifiably proud.

“So, of the 90,000 calls a year that came into the office for the five years you worked at the ME’s office before the day Dr. Norcroft called you, something on the order of half a million calls total, allowing for slack days and vacations, and the like, you handled upwards of 112,000?

To be conservative, let’s say more than 110,000?”

Tarkington enunciated the large number with stark clarity.

“Seem’s right.” Stringham had no idea where this was heading, but he thought that he was looking better all the time.

“Yeah, I been workin’ my buns off, like for years.”

“And of the 700 plus thousand calls fielded by your office since that day back in 2001, you had to have dealt with some 170,000 to 180,000, give or take a few?”

“Um-hmm,” Stringham muttered.

It was hard to keep his attention on the boring numbers.

“Please answer yes or no, so the stenographer can record your answer.”

“Yeah.”

“That’s a lot of calls.

Keeps you very busy, I presume, Am I right, Mr. Stringham?”

Mr. Tarkington seemed real friendly.

“Yeah. I’m a hard worker.

Like you got that right.”

“How is it, then, Sir, that out of nearly 250,000 to 300,000 calls that you yourself handled in those thirteen years of service, you remember that one lone call from Dr. Sybil Norcroft way back on September 8, 2001?”

Mr. Tarkington’s expression had turned hard, distinctly unfriendly now.

Stringham was beginning to feel like he had been had.

“I dunno, I just do.

That’s the long and the short of it.”

“Do you know Dr. Norcroft?

Were you familiar with Brendan McNeely or any of his family?

Was there anything, anything at all, special about that call?”

“I dint know none of them people.

Like they’re all too high and mighty for the likes of me.

I guess I remember how bitchy the lady doctor was.

Thought she was like such hot stuff.

That’s probably it, now that I think about it.”

“Was this the only bitchy doctor you ever dealt with, to use your phrase, Mr. Stringham, in all those thirteen years and 250,000 or 300,000 phone calls?”

“Naw, they all think their’s don’t stink.

Sorry, your honor.

They’re about all real snotty.

I just remember that one for some reason.”

“Maybe I could help you come up with that reason, Mr. Stringham.

Tell us, please, how many times did you meet with Mr. Bel Geddes, that’s the man over there at the defense table, the one with the handsome beard?”

The light bulb over Stringham’s head was beginning to turn on.

“Uh, well, maybe like about three times. I guess.”

“It was exactly three times, wasn’t it, Sir?”

“Yeah.”

“When was the last time?”

“‘Bout a month ago, best I recollect.”

“It was exactly nine days ago, isn’t that right?”

“If you say so.”

“What did you talk about in those meetings?

I see from Mr. Bel Geddes’s records that you spent about forty-five minutes each time. I guess you had a lot to discuss.”

“We talked about me rememberin’ about the doctor’s call to the ME’s office, stuff like that.”

“Did the name of Brendan McNeely come up?”

“Yeah.”

“More than once?”

“Yeah.”

“How about the name of the defendant, Dr. Sybil Norcroft, the lady brain surgeon?

Did it come up?”

“Yeah.”

“More than once?”

“Yeah.”

“In fact, didn’t both of those names come up many times in those three forty-five minute meetings?

Didn’t you, in fact, spend considerable time talking about them?”

“Yeah.”

“Did you contact Mr. Bel Geddes because you were a good citizen, and you remembered about that call, and thought that you had something to offer in the interests of justice?” Tarkington asked, his voice friendly again.

“Uh, well, no, like it wasn’t ‘zactly like that.”

“Exactly how was it?”

“He, uh…well, he sorta called me, called me first, near as I recollect.”

“And was it him, and by ‘him’ I mean the plaintiff’s attorney, that brought up the names, and not you?”

“Yeah.”

“One last question, and then you may step down, Mr. Stringham.

Are you being paid by Mr. Bel Geddes for being a witness?

Are you being paid more than you make at the ME’s office in a day?”

“Yeah.”

The next witness called by the plaintiff was the distinguished head of Ear, Nose, and Throat Surgery at Joseph Noble Memorial Hospital, Darryl James Hankin, M.D., F.A.C.S..

In direct testimony, he recounted the events surrounding the ill-fated transsphenoidal operation on Brendan McNeely.

His delivery was articulate and professional and unemotional.

Sybil’s mind wandered back in time to the actual events being scrutinized by the lawyers, the judge, and the jury on this uncomfortable day.

The surgery committee meeting following the unfortunate medical mishap and death of Brendan McNeely, RN, four days previously, was an unmitigated nightmare for Sybil Norcroft.

She had a pristine record, even her medical records were regularly kept up to date unlike 90% of her medical staff colleagues.

She had never been sued, never been the subject of a hospital, licensing board, or insurance disciplinary action in her five years of practice, and that made her a decided exception among her peers with five or more years in practice, especially her real peers, the neurosurgeons.

Scrutiny on doctors had become onerous from back as far as the Clinton presidential administration and seemed to worsen every year.

Sybil considered herself lucky to have escaped the spotlight until that night.

She remembered debating beforehand whether or not to go to the meeting.

She only had to attend fifty percent of the meetings to remain in good standing, and they were always deadly dull.

Her husband, Charles, had a meeting of his own; so, out of boredom, as much as anything else, she decided to attend.

The chart review and discussion of the financing of the new wing of surgical beds went by pro forma.

It looked as if it would be a short meeting, an idea that appealed to everyone present.

“Any further business?” Abdullah Sa’id, chairman of the surgery committee, asked.

“I do have one thing, Dr. Chairman, if I may?

Although the chart won’t appear for review until next month, I think this is something that should come to the committee’s attention tonight.”

It was Darryl Hankin from ENT speaking. He had been standing inconspicuously in the back.

“Go ahead, Darryl. No need to be so formal.”

“Thanks, Abdullah.

We get criticized for not policing ourselves, you all know.

I think I have a matter that needs some policing.

I want to get your slant on it.

It kind of embarrasses me to talk about this because the surgeon involved is here in the room, a committee member.

I’m sorry, Dr. Norcroft, but I think this should be brought out into the open.”

Sybil shot a glance at Dr. Hankin’s malevolently innocent face, handsome, and tanned. There flashed through her mind that this was payback time for her having supported his nurse in a sexual discrimination case she brought against her boss.

It had been a fiasco.

The good old boys of the patriarchy had marshaled their forces behind Hankin and had soundly whipped the nurse by producing half a score of women from his own office who denied that any such event ever took place.

Sybil had ended up looking like something of a fool to the rest of the medical community, even though she had earned her measure of accolades from the feminist community.

She knew that she had earned Hankin’s enmity for her part in the situation, but that had been three years ago, and she had figured that bygones were bygones. Evidently, she was wrong about that, her flash thought signaled.

“You have the floor and our full attention, Darryl, go ahead,” said Dr. Sa’id.

“Last Wednesday,” he began, and then recounted in exquisite detail all the events of the case.

Sybil could not fault him for lack of objectivity or for incompleteness.

“I find fault, and I’ve brought this up before, with the fact that Dr. Norcroft refuses to have a competent, and by that I mean, an M.D., assistant in her transsphenoidal cases.

She has always made it abundantly clear, including in public forum, that she considers the surgeons of my specialty to be nose pickers and that our services are superfluous.

Thus far she has been lucky. Until last Wednesday.

This case is the classical horrible example that proves the rule.

What concerns me, is the arrogance of the woman.

She seems to consider herself above the conventions, above cooperation, above the commonsense measures that all of us have to employ to protect our patients.

Much as I hate to do it, I am calling for a formal censure.

I am asking that Dr. Norcroft’s transsphenoidal privileges be suspended until her practices can be investigated.

If she is allowed to return to doing those delicate, and I tell you here, largely ENT, operations, then, I demand that she have an M.D., and preferably an ENT, specialist with her on every case.

I think the approach up the nose should be limited to ENTs.

That’s what I think.”

A burst of adrenaline swept through the collective veins of the surgery committee members.

It was unusual for a doctor to be criticized in public and so directly, and it was unheard of for a committee member to be humiliated right in front of the whole group.

Michael Strong, attending as the representative from administration, wrung his hands, fearing a potential law suit by Dr. Norcroft for defamation of character.

Abdullah Sa’id, the most polite and careful man in the western hemisphere fretted over the blatant breach of decorum.

The rest of the members of the committee were roused to a height of interest that none of them could recall having experienced in their three-year terms of office.

“Dr. Sa’id, fellow surgeons, I feel that I have been blind-sided by this.

I had no warning and have not made the slightest effort to defend myself nor my practice.

I won’t take up your time tonight, but I will prepare a written account and defense.

I’ll say this one thing tonight about the self-serving conclusion by the head of ENT.

I have to deal with the HMOs just like you do.

They control the expenses and the allotment of patients.

If I have an ENT assistant every time, I will quickly become too expensive for those blood sucker accountants in all the HMOs.

I won’t be allowed to do the cases; this hospital will lose the business; and no one will be better off.

Except possibly a few hungry ENT docs who get in on the few transsphenoidal cases before my practice and the hospital’s pituitary surgery business dies.

Think about that.

In my own defense, and from a pure medical standpoint, I am perfectly capable of doing the cases without an assistant’ and a scrub tech is more than enough.

They are very good, in case you haven’t noticed.

I’d match up Tanya Jenkins against any other assistant.

I think there are a number among you who would agree.”

“Until last Wednesday,” piped in Dr. Hankin, unwilling to be cheated out of the last word.

The meeting adjourned on that sour note.

Sybil submitted her defense, a document that became the property of the surgical committee and the hospital and never saw the light of day outside the institution, since internal investigatory documentation of hospitals is sacrosanct from outside exposure by statute.

While the document itself was carefully and self-servingly crafted and reworked until it portrayed Dr. Norcroft as a superbly qualified and capable surgeon victimized by the happenstance of a vascular anomaly, it was the nonstop political pressure that she brought to bear that saved her in the end.

It was a close thing.

The final vote for censure and for suspension of privileges was six for, eight against, one abstention–Dr. Sa’id–and two excused absences with three no-shows out of a twenty-member committee.

The charges, the debate, and the committee’s action never saw light in the public.

The only casualties were Sybil Norcroft’s stomach lining, and any pretense of comity or civility between her and Darryl Hankin.

Thereafter, the two surgeons would just as soon spit in the other’s eye as speak to one another.

“I have no further questions for this witness,” said Paul Bel Geddes indicating the end of his direct examination of Darryl Hankin.

“Dr. Hankin, would it be safe to say that you and Dr. Norcroft over there are on unfriendly terms?”

“I couldn’t argue with that characterization, counselor,” Hankin replied to Tarkington’s first question.

There were no preliminaries, no adjustment towards the hard questions to come.

“Wouldn’t it be more accurate that you hold each other in an attitude of mutual animosity?”

“That might be a little strong, but it’s not far off the mark.” Hankin’s handsome tanned face darkened as he looked over at Sybil Norcroft sitting expressionless at the defense table.

“Could that personal animus influence your testimony here today, Sir?”

“Not at all. I am reporting only the facts.”

“No bias?”

“None.”

“Have you ever become aware, of your own personal observation, of any other doctor or surgeon who has made a mistake or caused harm to a patient, or fell below the standard of practice for the community?

In all your twenty-one years of practice, Sir?”

“I might have. I suppose I have.

Nobody’s perfect.”

“Not even doctors?”

“Not even lawyers.”

“Touché.” Tarkington smiled.

Hankin relaxed a little and allowed himself a wan smile.

“Did you ever report any other doctor, any surgeon, any medical practitioner or provider of any kind or description to any official body for censure?”

“You mean other than Dr. Norcroft?”

“Other than her.”

“No.

Not that I can think of.”

“Ever criticize another doctor in a deposition?”

“No.”

“Ever testify publicly in court against another doctor?”

“Never.

Never had cause before.”

“I see. And it’s just coincidence that you are testifying against the defendant here today, and that you bear her ill will?”

“You could say that.”

Tarkington shook his head.

He was looking at the jurors at the time.

“Objection.

Counsel is conveying an opinion to the jury by his actions.”

“Mr. Tarkington, please stand away from the jury box.

Confine your activities to the question and answer format.

That’s how we do it in court.

Save the rest for the theater.”

“Yes, your honor,” Tarkington said.

He did not look as sheepish as his voice would have indicated.

“Dr. Hankin, were you in the operating room throughout the entire procedure performed on Mr. Brendan McNeely?”

“No, I wasn’t.”

“At what point did you enter the case?”

“When it was going to hell in a hand basket.”

“By that colorful turn of phrase do you mean after the onset of difficulties?”

“Yes.”

“So you did not see the opening of the case?”

“No.”

“Nor the approach to the floor of the sella turcica?”

“No.”

“Nor the removal of the sphenoid sinus bone, mucosa, or the bone of the sella?”

“No.”

“Did you, then, see the incision in the dura so that you could say exactly where that incision was made and whether or not it was done carefully and properly?”

“Well, not exactly.”

“We’re being exact here, Dr. Hankin.

This is a case about exactness. So am I correct in assuming that all you really saw of the pituitary operative site was a lot of blood issuing forth from the nasal opening?”

“Yes, but…”

“Yes, or no, Sir?”

“Yes.”

“And nevertheless, you consider yourself in a position to criticize the performance of that portion of the operation that you did not even see?”

“I know that transsphenoidal surgeries are not supposed to result in exsangination of the patient.

Any fool knows that.”

Hankin’s eyes glinted.

He seemed to be enjoying the game of confrontation although he had to admit to himself that, thus far, he was faring only middling well.

“Are there any possibilities as causes of the bleeding of which you can conceive other than those that mean malpractice on the part of the surgeon?”

“Well, I guess I could think of some.”

“But you have not mentioned any of those possibilities to this court, nor in deposition, have you?”

“No.”

“Would that seem to you to be the fair and objective evaluation of an impartial professional physician with no ax to grind?”

“Well, maybe not exactly.

I mean, I wasn’t there to talk about all the other possibilities.

I mean, it was about malpractice, wasn’t it?

I don’t recall ever being asked, now that I think about it.”

“I have only one more question, Dr. Hankin.

Actually, it’s a repeat of a previous question. I ask you once again, Sir, does bias and prejudice against this woman,” Tarkington drawled out and drew attention to the characterization of Sybil’s gender, “prompt you to give your critical testimony in the matter before this court?

Can you in all good conscience tell us that you are not influenced by your bad feelings towards her?”

“Yes. I mean, no,” Hankin stuttered, trying to unravel the pair of questions that hung over him like the proverbial, ‘have you stopped beating your wife?’

“Objection, compound question.”

“Sustained.”

“No further questions of this witness, your honor.”

“All right, strike that last question and answer. The jury will disregard the interchange. You may step down, Dr. Hankin.

Call your next witness, Mr. Bel Geddes.

“Heather Larkin, RN, CNRN,” the bailiff called out.

She entered through the main doors and strode purposefully to the witness stand.

Mrs. Larkin was sworn, her qualifications as a nurse and NICU administrator were presented ad nauseam, and the meaning of the initials after her name was elucidated with great amplification.

She testified for thirty-five minutes about two salient points: The first was that Dr. Norcroft had cut off the lifelines of the deceased prematurely, and in effect, murdered him.

The second was that Dr. Norcroft had insisted on calling the county medical examiner herself in order to obviate the performance of a postmortem examination to prevent the possibility of a gross surgical error being revealed.

She was a good witness–unemotional, but not uncaring.

She was convincing.

Sybil glanced at the spectators whenever she could without drawing attention to herself. Brendan’s family stared fixedly at Heather as she testified, looks of anguish on their faces.

The jurors were poor poker players as well.

Most of them had looks that bordered on anger.

Sybil began to worry.

“Your witness, counselor,” said Paul Bel Geddes.

“Thank you, counselor.

I have just a few questions, Mrs. Larkin.

You prefer Mrs. Larkin, don’t you?”

“I do.”

“You don’t fancy yourself much of a feminist, I take it.

You’re not a Ms., are you?”

“I’m not much impressed with that sort of thing, no, Sir.”

“You’re aware that the defendant, Dr. Norcroft, is something of a minor celebrity among people of the woman’s movement, are you not?”

“That’s an understatement.

She’s well known.”

“You don’t care for her or her feminist views, is that a fair statement?”

“That’s fair.

So what?

It has nothing to do with the facts of this case.”

“Um-hmm,” Tarkington mused. “Let’s get to the heart of the matter, ‘the facts of this case’, as you so adroitly put it.

You told this court that the defendant…excuse me, I’d like to be exact in quoting you.”

He made a small show of rifling through his notes.

“Ah, yes, you said, ‘She’, meaning the defendant, ‘might as well have put a pillow on his face.’ Do you recall making that statement?”

“Yes, and I meant every word of it.”

“Indeed. Are you familiar with the procedures employed to establish the diagnosis of brain death, in contradistinction to death of the organism?”

“Yes, it’s part of my training and work.

I see it and assist regularly. I am familiar, all right.”

There was a glint of antagonism in Heather’s cold grey eyes.

“Did Dr. Norcroft’s notes indicate a significant deviation from the practice involved in making the diagnosis of brain death?”

“Not in her notes.”

“Did her notes reflect falsely, that is, did she do one thing and record another?”

“No, not exactly, but…”

“Did she do multiple neurological examination physical tests over an extended period of time?”

“She did.”

“An EEG? A repeat EEG?”

“She did all of that.”

“Was her procedure in this case substantially at variance with that done by other qualified doctors who work in the NICU?”

“No, except…”

“Different than her own usual standards of practice?”

“Not exactly, but…”

“What was it that led you to make such a serious charge, in effect accusing this doctor of committing murder, Mrs. Larkin?”

“Thank you for finally letting me answer,” Heather said testily.

Tarkington nodded infuriatingly.

“The doctor was in such an all-fired rush to get rid of Brendan so that everyone would not have to come by and bear witness to her colossal mistake, that she ignored signs of life.

She pronounced him dead and removed his life supports when he was still alive.”

There was a chilly stillness in the air-conditioned courtroom, much as there had been when Mrs. Larkin conveyed her inflammatory testimony during direct examination by Paul Bel Geddes. There was not a sound in the courtroom. It was as if they were collectively holding their breath.

“Yes, that sign of life.

I believe Dr. Norcroft made note of that in her last progress note…no, the next to the last, where she describes the final brain death examination.

She describes some motor movement that she says is ‘primitive,’ a ‘primitive, peripheral reflex.’

I take it you don’t hold with the notion that there can be movement below the neck in a patient that is brain dead.

Is that a fair statement, Mrs. Larkin?”

“Sometimes a little old-fashioned horse sense needs to be used, Mr. Tarkington.

It isn’t all gadgets and technology or cookbook, even in the twenty-first century.

Brendan moved right before the end, even without being stimulated.

He was alive.”

She glared her defiance at the attorney.

“But the two doctors, two, mind you, both neurosurgeons, disagreed with you, didn’t they?”

“Yes.”