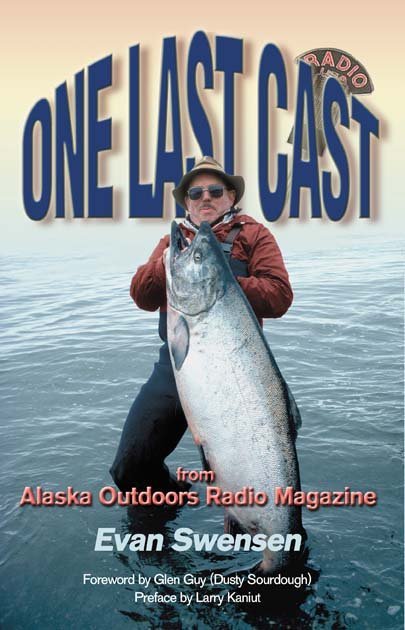

One Last Cast

From Alaska Outdoors Radio Magazine

By Evan Swensen

Chapter Seventy-Eight

The First Catch and Release

Mt. McKinley’s 20,320-foot summit guards the Interior’s southern flank, and the Brooks Range stands watch to the north. East is the Yukon border, and the west converges to the Bering Sea. Most of the country is covered with low, rolling hills. Braided rivers cross the country on their way to the sea. The great rivers of the gold rush: Yukon, Tanana, Porcupine, Koyukuk, and others, still serve as much of the Interior’s only highways.

Interior’s summer is a paradox—short in number of days but long in hours of daylight per day. Almost 24 hours of light bless anglers who want to fish ’round the clock. This is the place to take off your watch and, without thought of time, fish when you want.

Unless a timepiece is consulted, far-north adventures cannot tell the time of day. While fishing the Interior, anglers may fish until midnight under a brilliant sun. The sun will set slowly and turn pink or red behind northern hills, only to hesitate and begin its upward climb as a stunning sunrise.

What rainbow trout are to Western Alaska, pike, grayling, and sheefish are to the Interior. Northern pike weighing up to 30 pounds and more may be taken. In season, some area lakes and streams will be choked with migrating grayling. Sheefish haunt the Yukon River and its tributaries, the lower Chena River, and Minto Flats streams. Rainbow, not indigenous to the area, have been planted in many lakes along the road system.

Vermont colors pale when compared to an Interior fall. Although short, the period between long sunny summer days and freeze-up is an outstanding display of Mother Nature’s colors. Every color in God’s paint pot is on parade in a procession of public performances that brings goose bumps to all but the most jaded observer. Across the tundra and through the trees and brush, travelers are treated to exhibitions of tincture from octopus black to celestial white, from blazing blue to flaming red to scorching yellow. If there was ever a time and place for an artist to witness every imaginable hue and color, Interior in the fall meets the exact criteria.

While waiting for our ride at the end of an Interior fall outing, we gathered bits and pieces of tundra color. During the doldrums of waiting, three of us fashioned an arctic scavenger hunt. We crossed and crisscrossed the tundra and retrieved morsels of color to photograph for an outstanding representation of the area’s coloring. After an hour of searching, we returned to camp and assembled a composition almost impossible to paint. Nevertheless, we marveled at the variety of hues, tones, tints, tinges, and density. The resulting photograph is one of my favorites.

Angling the Interior is fishing in a country unpopulated and waters truly unpolluted. One of my choicest Alaska outings was fishing the far north with a native Alaskan guide. We were on the Fish River and its tributaries. My guide had learned the river from his grandparents, who learned from their grandparents, yet his skill with a fly rod and spinning rod was as modern as tomorrow. We were fishing a little “Southeast of Nome” on a river named Fish, in country like all Alaska used to be but will never be again.

Paul, my guide, passed on to me the ancient Eskimo catch and release custom he learned from his grandmother, who learned it from her grandmother, and so on back to the beginning. Ancient Eskimo fishermen returned the first fish they caught, believing it would tell the other fish how well he was treated, and the others would come to find out for themselves.

My fishing partner and I decided that if it worked by releasing the first fish, we would find out what would happen if we released all the fish we caught. The results were so outstanding that we can now write a new chapter in the book on reasons for catch and release. Turn back the fish you capture; they will go and tell the rest how well they were treated, and the others will seek you out.

Paul’s grandmother, fishing with primitive instruments, may have known something we could learn about our angling pursuits in our age of boron and ball bearings. In Interior Alaska, on the Fish River, a little southeast of Nome, catch and release predated Trout Unlimited by centuries.